Incendie du Cap, Saint-Domingue, ou histoire de ses revolutions, 1815.

A “bellum servile,” or large-scale rebellion, was the type of slave resistance Jefferson feared most. Only 3 of the 607 enslaved people he owned in his lifetime were ever accused of “… rebelling and making insurrection.” Instead, most of the men, women, and children living on his plantations resisted the de-humanizing effects of slavery in other ways.

Dozens of slaves resisted their bondage by running away. To claim their freedom during the American Revolution, 19 of Jefferson’s slaves joined British forces in exchange for liberty. Most of the enslaved people who ran away from Jefferson’s plantations did so to see wives, husbands, fathers, mothers, and children living far from Monticello. They resisted the separation of families, one of the most disturbing aspects of slavery.

Theft was one way that enslaved people protested the limits that bondage placed on access to food and material goods. Jefferson recorded thefts from locked corn cribs, charcoal sheds, smokehouses, poultry yard, nailery, wash house, and storage cellars.

Most bondspeople likely practiced some day-to-day resistance. Slaves collaborated to set their work pace, to improve their working conditions, and to maintain plantation privileges. Many men, women, and children negotiated their situations, using their statuses as skilled laborers to diminish workloads, benefit family members, or to gain access to material goods.

Enslaved people owned by Jefferson seldom resorted to violence. But in 1822, Hercules and two other Poplar Forest slaves attacked the overseer and were charged with stabbing and intent to kill and "wickedly and feloniously having consulted upon the subject of rebelling and making insurrection against the law and government of...Virginia." Hercules and Gawen were found not guilty, while Hannah's Billy, who had wielded the knife, was sentenced to burning "in the left hand" and 39 lashes for all counts except conspiracy.

In 1806, Jefferson’s trusted blacksmith, Joseph Fossett, ran away from Monticello. "I send Mr. Perry in pursuit of a young mulattoe man named Joe, 27. years of age,” Jefferson wrote, “who ran away from here the night of the 29th. inst[ant] without the least word of difference with anybody, and indeed having never in his life recieved a blow from any one." Fossett ran away to Washington, D.C., where his wife, Edith, worked in the President’s House (now the White House) kitchen and took care of the couple’s young son, James.

Videos about Resistance at Monticello

A Blacksmith Slips Away

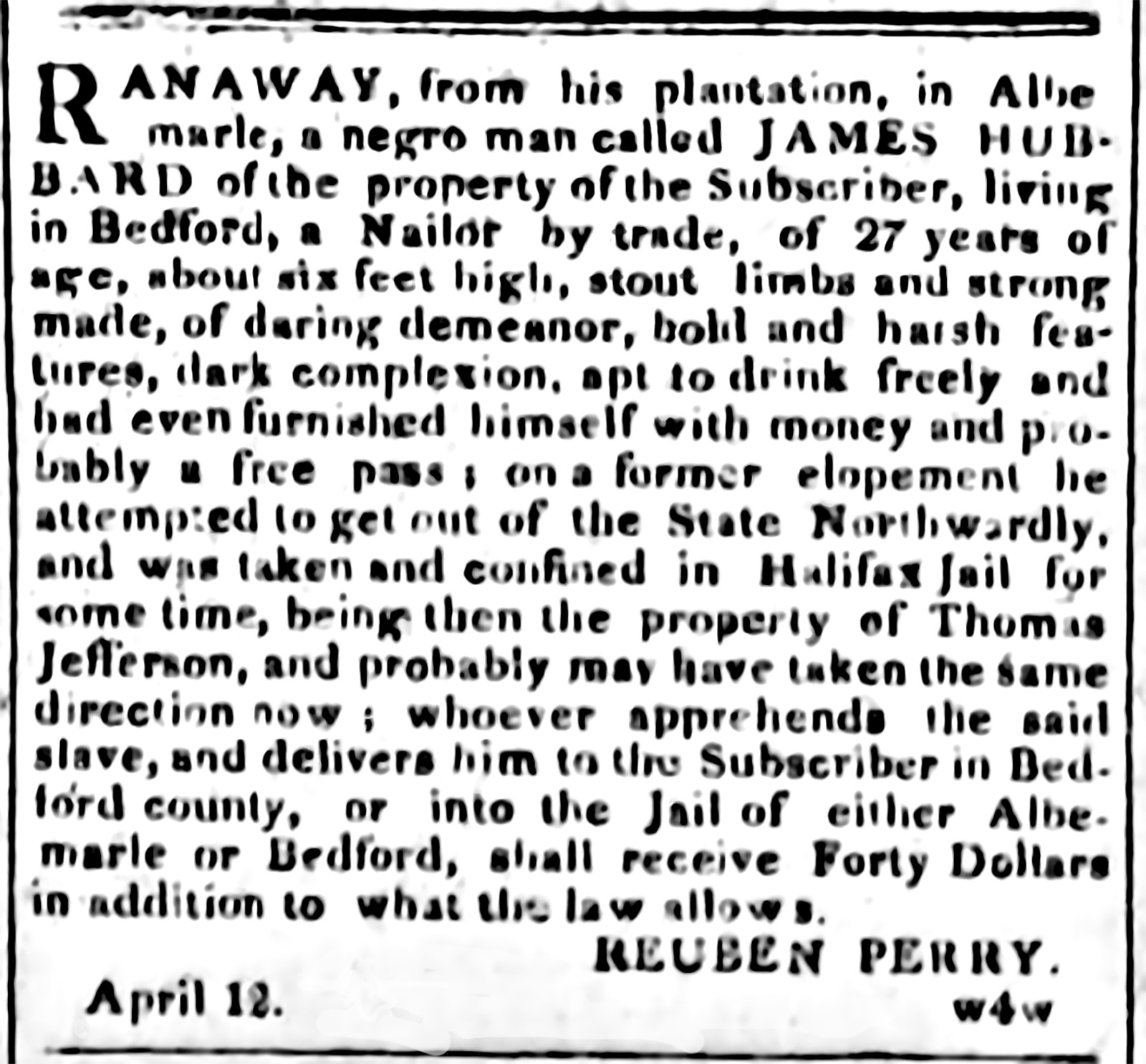

James Hubbard's Carefully Planned Escape

"Of daring demeanor" - James Hubbard Attempts a Second Escape