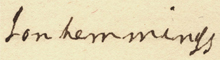

A highly skilled joiner and cabinetmaker, Hemmings was the youngest son of Elizabeth (Betty) Hemings; his nephew Madison reported that his father was Joseph Neilson, a hired English carpenter. More is known about Hemmings than any other enslaved person at Monticello as he left behind a dozen letters and was often mentioned in family correspondence. A field worker as a child, he later was one of a “gang” of “out-carpenters” felling trees for firewood, fences, and charcoal; hewing logs; and erecting log buildings, including slave dwellings r, s, and t on Mulberry Row. In 1793, he learned joining as an apprentice to hired joiner David Watson, and later from James Dinsmore, the Irish joiner who carried out the construction of Monticello II (1798–1809). Hemmings succeed Dinsmore. Overseer Edmund Bacon remembered him as "a first-rate workman--a very extra workman. He could make anything that was wanted in woodwork." In addition to architectural woodwork in the main house, Hemmings made a carriage, a special writing desk for Ellen Randolph Coolidge, furniture, and Jefferson’s coffin. He was given his freedom in Jefferson’s will together with the tools of his trade. He and his wife Priscilla, nursemaid to the Randolph children, had no children; Hemmings made the stone marker for her grave.

This account is compiled from Lucia Stanton, “Those Who Labor for My Happiness:” Slavery at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello (University of Virginia Press and Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2012).

Videos about John Hemmings

The Elliptical Arch in Monticello's Library

"I remember the interior of that cabin" - Finding a Lost Diary