On a cold day in mid-January 1827, members of the Charlottesville community made their way to Monticello to attend the estate sale of Thomas Jefferson. Announced in newspaper advertisements in late 1826, the sale consisted of furniture, kitchen wares, farm equipment, livestock, “curious and useful” articles, and, most tragically, “130 valuable negroes.”

This sale tore apart families, separated husbands and wives and parents and children, and created a diaspora of Monticello’s enslaved community.

"the most valuable for their number ever offered

at one time in the State of Virginia"

The impetus for the sale was simple: Jefferson’s enormous debt, which had ballooned to $107,000 (more than $2,000,000 in 2019 dollars) by the time of his death. Poor financial decisions, inadequate agricultural income, a financial panic, and a lavish lifestyle led to this moment. As was customary at the time, Jefferson's debt became the responsibility of his heirs—and a living nightmare for the men, women, and children held in bondage who knew they would be sold to cover that debt.

The Sale

“...put upon an auction block and sold to strangers. ”

Potential buyers included Thomas Jefferson’s family and friends, professors from the recently opened University of Virginia, a man formerly enslaved at Monticello, and the free relatives of enslaved persons about to be sold.

In total, nearly 100 people were sold in bidding that took place over five days. (The original advertisement noted the sale of 130 persons, but at least 33 more people were sold two years later in downtown Charlottesville.)

No written document can convey the pain, suffering, and enduring trauma that resulted from these sales. Yet primary sources do shed light on the sales themselves and the fate of Monticello’s enslaved community.

Pre-printed Bill of Sale for Purchase of Slaves from Thomas Jefferson’s Estate

Gallery of auction-related documents and images

The Fossetts

Joseph Fossett's entire family was up for sale, and he was likely in attendance. Fossett had worked for many years as a skilled blacksmith Monticello. He was to be freed according to Jefferson’s will, but not until July 1827, and the task of bidding for Fossett’s family fell to Jesse Scott, the husband of Fossett’s free half-sister, Sarah Bell Scott. She was the daughter of Fossett's mother, Mary Hemings Bell, and Thomas Bell, a white merchant in Charlottesville. Together, the Fossett, Bell, and Scott families raised and borrowed money to buy their family members’ freedom. Yet, in the end they did not have sufficient funds. They were only able to buy Fossett’s wife, Edith, and their two youngest children. Over the next 23 years, the Fossetts continued to work to buy and reunite their family.

Four of Fossett's other children—Ann-Elizabeth, Martha (Patsy), Isabella, and Peter Fossett—were purchased by separate buyers at the 1827 sale.

Ann-Elizabeth was purchased by a local merchant at the 1827 sale but gained her freedom with help from her family and followed them with her husband and children to Ohio in 1840.

Within a year, Martha (Patsy) had run away from the man who bought her. Her travels ultimately took her to Gold Rush–era California, where she made a fortune and married a white man.

Isabella escaped to Boston in the 1840s using papers forged by her brother Peter. She later made her way to Cincinnati.

Peter Fossett attempted to run away on two occasions. After his second failed attempt in 1850, he was purchased at auction by family friends and moved to Ohio. He ultimately became one of Cincinnati’s most prominent caterers, a conductor on the Underground Railroad, and a renowned Baptist minister. His reminiscences, published almost exactly 71 years after his first sale at Monticello, are a vivid account of his life during and after slavery.

The Gillettes

Seven members of the Gillette family were offered for sale at the auction. With no free relatives to help buy their freedom, each was sold to a different buyer.

James Gillette ran away from his owner in Richmond shortly after being purchased.

Moses Gillette was purchased by a miller in Charlottesville and remained in slavery until the end of the Civil War, when he moved to Ohio to live near his brother, Israel.

Israel Gillette was sold to Thomas Walker Gilmer, a prominent resident of Albemarle County, who served as Virginia’s Governor and later as the U.S. Secretary of the Navy. With the help of his second wife, a free woman of mixed European and African heritage, Gillette was able to purchase his freedom from Gilmer on credit.

Gillette’s first wife was an enslaved woman with whom he had four children. In his reminiscences, published in 1873, he alluded to the cost of having children in slavery. “As they were born slaves they took the usual course of most others in the same condition in life. I do not know where they now are, if living; but the last I heard of them they were in Florida and Virginia.” He added, “When my first wife died I made up my mind I would never live with another slave woman.”

The Hemingses

Peter Hemings, Sally Hemings's brother, was the only Hemings male from his generation sold at the 1827 auction. Like many in his family, Hemings played prominent roles at Monticello. He had learned cooking from his brother James and brewing from an English brewmaster. Jefferson described him as possessing "great intelligence and diligence." But while six of his siblings had either gained freedom or been given their time by 1827, Peter Hemings's fate, like those of his Fossett cousins, rested on the help of family. A nephew, possibly the son of Mary Hemings Bell, purchased Hemings for a one dollar—likely through a special agreement with Thomas Jefferson Randolph—and granted him his freedom. Hemings spent the remaining seven years of his life working as a tailor in Charlottesville.

Critta Hemings Bowles gained her freedom after it was bought by Jefferson's grandson, Francis Eppes, for fifty dollars. Bowles had served as Eppes's nurse when he was an infant, 25 years earlier. The manumission deed referred to "Critty, some times called Critty Bowles, the wife of Zachariah Bowles a free man of colour" living in Albemarle County. After obtaining her freedom, she lived with her husband on his property until her death in 1850 at the age of 81.

After Monticello

The 1827 sale at Monticello was the largest of the efforts to settle Jefferson's estate and debts. But it wasn't the last. Over the next four years—in sale after sale—furnishings, books, paintings, land, and humans were offered for purchase. At least three other auctions appeared to have been held by early 1829: two at Poplar Forest (Jefferson's plantation in Bedford County Virginia) and one in downtown Charlottesville.

Finally, in 1831, Monticello and 500 surrounding acres sold for $7,500. The 1829 Charlottesville auction alone raised $8,300 from the sale of 33 individuals. That just a fraction of his human property raised more than the sale of his house and land speaks directly to the immense wealth these individuals represented at the time. According to one estimate, the enslaved men, woman, and children who lived at Monticello represented 90 percent of the appraised value of Jefferson's Albemarle County properties.

At the time of his death, Jefferson owned approximately 200 individuals. Of the 130 offered for sale from the Monticello plantation in 1827 and 1829, the fates of 55 are unknown. A further 70 individuals were advertised for sale in 1827 from his Poplar Forest plantation near Lynchburg, VA, but no accounts or records from that sale exist today.

Most of the enslaved families of Monticello were scattered in many directions and separated—sometimes for decades and often permanently—by distance, by freedom and bondage, and by color lines.

Getting Word

Monticello is fortunate to work with descendants of Monticello’s enslaved community through the Getting Word African American Oral History Project, now in its 26th year.

Through Getting Word, the descendant community has indelibly shaped Monticello’s scholarship and interpretation. Because of their contributions, we know details about the lives of people who were enslaved here – stories of work, struggle, hope, and dreams that have added an essential human dimension to our understanding of life at Monticello. Their stories tell of an American struggle to make real Jefferson’s words about liberty and equality.

Descendants participated in the Underground Railroad, served as officers in both black and white regiments during the Civil War, and were actively involved in the creation of the Civil Rights Movement. They built businesses, worked their own farms, pursued careers in the arts, and founded churches that still thrive today.

Getting Word African American Oral History Project

To date almost 200 people have participated in this project. Hear their stories and trace their families from slavery to the present day.

Read more about it:

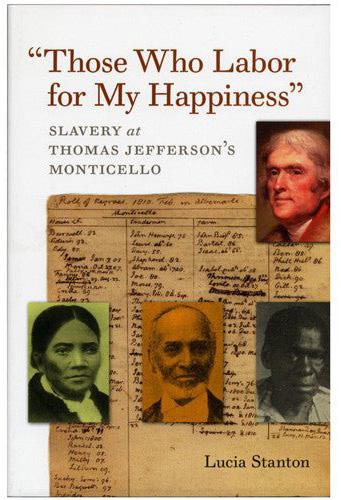

"Those Who Labor for My Happiness"

"Those Who Labor for My Happiness" - Slavery at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello by Lucia Stanton explores the lives of the individuals Thomas Jefferson relied upon to build and run his plantation and household, and follows their remarkable stories from Monticello's beginnings to Jefferson's time in Washington, DC, through to the aftermath of the American Civil War.