Wine

Thomas Jefferson claimed, in 1818, that "in nothing have the habits of the palate more decisive influence than in our relish of wines."[1] His own habits had been formed over thirty years before — at the tables of Parisian philosophes and in the vineyards of Burgundy and Bordeaux. Before his journey to France in 1784, Jefferson, like most of his countrymen, had been a consumer of Madeira and port, with the occasional glass of "red wine." As he recalled in 1817, "[T]he taste of this country [was] artificially created by our long restraint under the English government to the strong wines of Portugal and Spain."[2]

The revolution in his own taste in wine followed swiftly on the breaking of the bonds of British colonial government. Thereafter Jefferson rejected the alcoholic wines favored by Englishmen as well as the toasts that customarily accompanied them. He chose to drink and serve the fine lighter wines of France and Italy, and hoped that his countrymen would follow his example.

While it is often difficult to distinguish the wines Jefferson preferred for the sake of his own palate from those he purchased for the comfort of his dinner guests, the quotations that follow should help to identify some of his personal favorites, as well as to illustrate the standards of reference for his taste in wine and his efforts to redeem the taste of his countrymen.

- - James A. Bear, Jr., 1984. Originally published as "Reforming the Taste of the Country," in Fall Dinner at Monticello, November 2, 1984, in Honor of James A. Bear, Jr. (Charlottesville, VA: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation), 1-9.

Thomas Jefferson and Wine

In this live conversation, Thomas Jefferson, as interpreted by Bill Barker, discusses his long fascination with wine and viticulture.

1803. Writing to a correspondent in Spain, Jefferson confessed that a certain pale sherry had "most particularly attached my taste to it. I now drink nothing else, and am apprehensive that if I should fail in the means of getting it, it will be a privation which I shall feel sensibly once a day."[3]

1806. Jefferson described a recent shipment of Nebbiolo, a sparkling wine of the Italian Piedmont, as "superlatively fine."[4] This importation proceeded from his memory of drinking Nebbiolo in Turin in 1787, when he described it as "about as sweet as the silky Madeira, as astringent on the palate as Bordeaux, and as brisk as Champagne. It is a pleasing wine."[5]

When paying a bill for three pipes of Termo, a Lisbon wine drier and lighter than ordinary port, Jefferson said that "this provision for my future comfort" had been sent to Monticello to ripen.[6]

Monticello's Wine Cellar

1815. By this time, after years of war had prevented importation, Jefferson's stock of aged Lisbon and leftovers from the President's House was exhausted. Writing to a Portuguese wine merchant in Norfolk, he said, "Disappointments in procuring supplies have at length left me without a drop of wine. I must therefore request you to send me a quarter cask of the best you have. Termo is what I would prefer; and next to that good port. besides the exorbitance of price to which Madeira has got, it is a wine which I do not drink, being entirely too powerful. wine from long habit has become an indispensable for my health, which is now suffering by it’s disuse."[7]

For his major supply, he wrote to Stephen Cathalan, the American agent at Marseilles:

I resume our old correspondence with a declaration of wants. the fine wines of your region of country are not forgotten, nor the friend thro’ whom I used to obtain them. and first the white Hermitage of M. Jourdan of Tains, of the quality having ‘un peu de la liqueur’ as he expressed it, which we call silky, soft, smooth, in contradistinction to the dry, hard or rough. what I had from M. Jourdan of this quality was barely a little sweetish, so as to be sensible and no more; and this is exactly the quality I esteem. Next comes the red wine of Nice, such as my friend mr Sasserno sent me, which was indeed very fine. that country being now united with France, will render it easier for you I hope to order it to Marseilles. There is a 3d kind of wine which I am less able to specify to you with certainty by it’s particular name. I used to meet with it at Paris under the general term of Vin rouge de Roussillon; and it was usually drunk after the repast as a vin de liqueur, as were the Pacharetti sec, & Madeire sec: and it was in truth as dry as they were, but a little higher colored. I remember I then thought it would please the American taste, as being dry and tolerably strong. I suppose there may be many kinds of wine of Roussillon; but I never saw any but of that particular quality used at Paris. I am certain it will be greatly esteemed here, being of high flavor, not quite so strong as Pacharetti or Madeire or Xeres, but yet of very good body, sufficient to bear well our climate.[8]

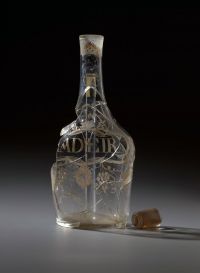

Madeira decanter fragments by Monticello archaeologists during excavations outside Monticello's South Wing

Madeira decanter fragments by Monticello archaeologists during excavations outside Monticello's South WingThe Hermitage, which he had regularly imported while President, was described by Jefferson in 1791 as "the first wine in the world without a single exception."[9] The Bellet from Nice he called "the most elegant every day wine in the world."[10] The Roussillon, which he continued to import, was evidently bought for the sake of his guests as an intermediate stage in the Madeira weaning process.

1816. "[F]or the present I confine myself to the physical want of some good Montepulciano ... , this being a very favorite wine, and habit having rendered the light and high flavored wines a necessary of life with me."[11] Jefferson had imported this red Tuscan wine as President and had declared an 1805 shipment "most superlatively good."[12]

1817. Jefferson gave the state of North Carolina credit for producing "the first specimen of an exquisite wine," Scuppernong, and praised its "fine aroma, and chrystalline transparence."[13] Writing to his agent in Marseilles about a recent shipment of Ledanon, a wine produced near the Pont du Gard, Jefferson declared it "excellent" and said it "recalled to my memory what I had drunk at your table 30. years ago, and I am as partial to it now as then."[14] Elsewhere he described this vin de liqueur as having "something of the port character but higher flavored, more delicate, less rough."[15]

Speaking of the French wines of Hermitage, Ledanon, Roussillon, and Nice, he stated that he was "anxious to introduce here these fine wines in place of the alcoholic wines of Spain and Portugal; and the universal approbation of all who taste them at my table will, I am persuaded, turn by degrees the current of demand from this part of our country, [an]d that it will continue to spread de proche en proche. the delicacy and innocence of these wines will change the habit from the coarse & inebriating kinds hitherto only known here." He added that he would order the white Hermitage only occasionally, it "being chiefly for a bonne bouche."[16]

1819. No single letter provides a better statement of Jefferson's drinking habits, his tasting vocabulary, and his efforts to convert his fellow Americans than one written on May 26 to Stephen Cathalan:

... I will explain to you the terms by which we characterise different qualities of wines. they are 1. sweet wines, such as Frontignan & Lunel of France, Pacharetti doux of Spain, Calcavallo of Portugal, la vin du Cap Etc. 2. Acid wines, such as the Vins de Graves, du Rhin, de Hocheim Etc. 3. dry wines, having not the least either of sweetness or of acidity in them, as Madere sec, Pacharetti sec vin d’Oporto, Etc. and the Ledanon which I call a dry wine also. 4. silky wines, which are in truth a compound in their taste of the dry wine dashed with a little sweetness, barely sensible to the palate. the silky Madeira which we sometimes get here, is made so by putting a small portion of Malmsey into the dry Madeira. there is another quality of wine which we call rough, or astringent, and you also, I believe, call it astringent, which is often found in both the dry & the silky wines. there is something of this quality for example in the Ledanon, and a great deal of it in the vin d’Oporto, which is not only dry, but astringent approaching almost to bitterness. our vocabulary of wines being thus explained, I will observe that the wine of Nice sent me by mr Spreafico in 1816. was silky and a little astringent and was the most delicious wine I ever tasted, and the most esteemed here generally. that of 1817. was entirely dry, moderately astringent and a very good wine; about on a footing with Ledanon. that of 1818. last recieved, has it’s usual astringency indeed, but is a little acid, so much so as to destroy it’s usual good flavor. had it come in the summer I should have suspected it’s having acquired that acidity by fretting in the hold of the ship, or in our hot warehouses on a summer passage. but it was shipped at Marseilles in October, the true time for shipping delicate wines for this country. I will now say why I go into these details with you. in the first place you are not to conclude that I am become a buveur my measure is a perfectly sober one of 3. or 4. glasses at dinner, & not a drop at any other time. but as to these 3. or 4. glasses Je suis bien friand. I go however into these details because in the art, by mixing genuine wines, of producing any flavor desired, which mr Bergasse possesses so perfectly, I think it probable he has prepared wines of this character also; that is to say of a compound flavor of the rough, dry, and sweet, or rather of the rough and silky; or if he has not, I am sure he can. the Ledanon, for example, which is dry and astringent, with a proper proportion of a wine which is sweet and astringent, would resemble the wine of Bellet sent me in 1816. by mr Spreafico. if he has any wines of this quality, I would thank you to add samples of 2. or 3. bottles of each of those he thinks approaches this description nearest. ... I have labored long and hard to procure the reduction of duties on the lighter wines, which is now effected to a certain degree. I have labored hard also in persuading others to use those wines. habit yields with difficulty. perhaps the late diminution of duties may have a good effect. I have added to my list of wines this year 50. bottles of vin muscat blanc de Lunel. I should much prefer a wine which should be sweet and astringent. but I know of none. if you know of any, not too high priced I would thank you to substitute it instead of the Lunel.[17]

Unfortunately Henri Bergasse, a producer of blended wines, did not make the desired wine and the death of Cathalan prevented a personal response to Jefferson's request for the perfect "rough and silky" wine. Cathalan's successor sent samples of several wines and from these Jefferson selected a Clairette de Limoux, which he found "much to our taste" and continued to order, but which does not seem to have satisfied his personal quest for perfection.[18]

1826. With the exception of a "sufficient" quantity of Scuppernong, all the wines on hand in the Monticello cellar at the time of Jefferson's death came from southern France: red Ledanon, white Limoux, Muscat de Rivesalte, and a Bergasse imitation red Bordeaux. This cellar list and the preceding letters seem to confirm evidence of family members and visitors to Monticello that, at least in his later years, Jefferson drank wine at table only after the completion of the meal, in the English manner. His habits still reflected his British heritage but his tastes were international. High in flavor but low in alcohol, the wines of France and Italy were the perfect accompaniment to social pleasure and the "true restorative cordial," as he designated both wine and friendship.

Further Sources

- Lawrence, R. De Treville. Jefferson and Wine: Model of Moderation. The Plains, VA: Vinifera Wine Growers Association, 1989. More than 30 essays on various aspects of Jefferson and wine.

- Gabler, James M. Passions: The Wines and Travels of Thomas Jefferson. Baltimore: Bacchus Press, 1995. Especially useful appendices at the end, including a listing of Jefferson's favorite wines that are still available today, and an annotated listing of wines in the White House cellar.

- Hailman, John R. Thomas Jefferson on Wine. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2006. An excellent overview of Jefferson's lifelong appreciation and pursuit of wine.

- Stanton, Lucia. Research Report: Chateau Lafite 1787, with initials "Th. J." Unpublished report, Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 1985.

- Look for further sources on Jefferson and wine in the Thomas Jefferson Library Portal or at The Shop at Monticello..

References

- ^ Jefferson to William Alston, October 6, 1818, in PTJ:RS, 13:302. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Stephen Cathalan, [before June 6, 1817], in PTJ:RS, 11:404. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Joseph Yznardi, May 10, 1803, in PTJ, 40:356. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Thomas Appleton, October 26, 1806, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson, Notes of a Tour into the Southern Parts of France, &c., March 3–June 10, 1787, in PTJ, 11:435. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to William Jarvis, April 16, 1806, Privately owned. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to John F. Oliveira Fernandes, December 16, 1815, in PTJ:RS, 9:263. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Cathalan, July 3, 1815, in PTJ:RS, 8:570-71. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson, Memorandum on Wine, [after April 23, 1788], in PTJ, 27:762. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to James Monroe, April 8, 1817, in PTJ:RS, 11:246. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Appleton, January 14, 1816, in PTJ:RS, 9:350-51. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Appleton, May 4, 1805, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to William Johnson, May 10, 1817, in PTJ:RS, 11:345. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Cathalan, [before June 6, 1817], in PTJ:RS, 11:404. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Monroe, April 8, 1817, in PTJ:RS, 11:246. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Cathalan, [before June 6, 1817], in PTJ:RS, 11:405-06. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Cathalan, May 26, 1819, in PTJ:RS, 14:327-30. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Joshua Dodge, July 13, 1820, Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society. Transcription available at Founders Online.