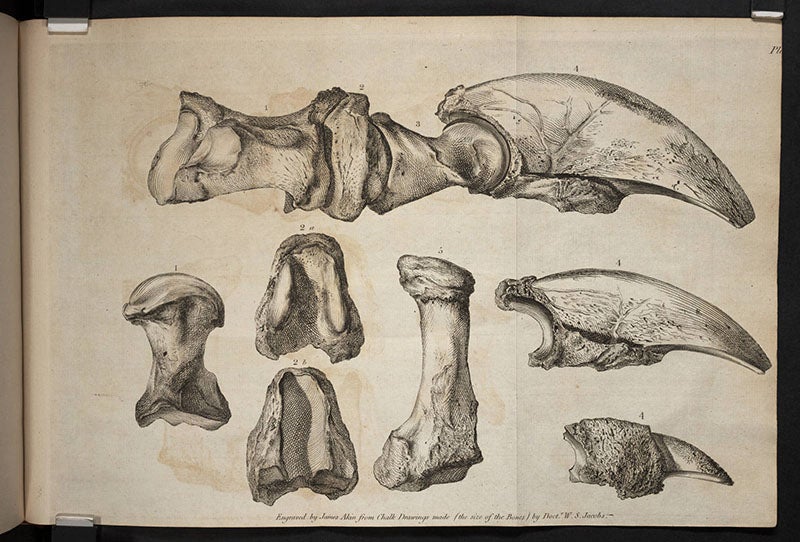

Megalonyx Jeffersonii Fossils

Once Notes on the State of Virginia was available in the United States in 1787, Thomas Jefferson's interest in fossils became widely known. For more than two decades Jefferson received fossils from friends and acquaintances who knew of his curiosity. An odd gift came from Colonel John Stuart of Greenbrier County, Virginia (now West Virginia):

Once Notes on the State of Virginia was available in the United States in 1787, Thomas Jefferson's interest in fossils became widely known. For more than two decades Jefferson received fossils from friends and acquaintances who knew of his curiosity. An odd gift came from Colonel John Stuart of Greenbrier County, Virginia (now West Virginia):

Being informed you have retired from public Business and returned to your former Residence in Albemarle, and observing by your Notes your very curious desire for Examining into the antiquitys of our Country, I thought the Bones of a Tremendious animal of the Clawed kind lately found ... might afford you some amusement ....[1]

Stuart added that he thought the animal was "of the Lion kind."[2] Jefferson began preparing a paper on the bones, based on Stuart's hypothesis, for submission to the American Philosophical Society.

Stuart added that he thought the animal was "of the Lion kind."[2] Jefferson began preparing a paper on the bones, based on Stuart's hypothesis, for submission to the American Philosophical Society.

While waiting in vain for Stuart to send a thigh bone of the animal that could indicate its full size,[3] Jefferson was elected to two important offices: vice president of the United States under John Adams and president of the American Philosophical Society. With his induction as Society president pending, Jefferson completed his paper on the bones with the information at hand and carried the fossils with him on the journey to Philadelphia. He had reached the conclusion that the bones were from an animal "of the lion kind, but of most exaggerated size."[4] Because of the animal's bulk — three times that of a lion — Jefferson called it "the Great-claw or Megalonyx."[5]

Some time after his arrival in Philadelphia in March 1797, Jefferson went to a bookstore where he happened to peruse the September 1796 issue of London's Monthly Magazine. By incredible coincidence the issue contained an engraving of a fossilized skeleton that was strikingly similar to Jefferson's "Megalonyx," but it was identified as a relative of the sloth. The fossils from Paraguay illustrated in Monthly Magazine had been mounted in the Royal Cabinet of Natural History in Madrid. Realizing that his classification of the fossils as part of the cat family was probably wrong, Jefferson quickly revised his paper on the day of his presentation. He deleted all references to "Megalonyx" and substituted instead the more general term, an animal "of the clawed kind."[6]

The bones were deposited in the Society's collection. The renowned Dr. Caspar Wistar noted both similarities and differences between the bones at hand, those of a sloth, and those illustrated in Monthly Magazine, leaving the identification of the specimen unanswered.[7] In 1804 Jefferson was credited as the discoverer of the Megalonyx, an animal that is indeed related to the sloth family, and in 1822 the French naturalist Anselme Desmarest gave the extinct animal its formal name: Megalonyx jeffersonii.[8]

The bones were deposited in the Society's collection. The renowned Dr. Caspar Wistar noted both similarities and differences between the bones at hand, those of a sloth, and those illustrated in Monthly Magazine, leaving the identification of the specimen unanswered.[7] In 1804 Jefferson was credited as the discoverer of the Megalonyx, an animal that is indeed related to the sloth family, and in 1822 the French naturalist Anselme Desmarest gave the extinct animal its formal name: Megalonyx jeffersonii.[8]

- Text from Stein, Worlds, 398, 400

References

- ^ Stuart to Jefferson, April 11, 1796, in PTJ, 29:64. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ See Jefferson to Stuart, November 10, 1796, in PTJ, 29:205-06. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, January 22, 1797, in PTJ, 29:275. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to David Rittenhouse, July 3, 1796, in PTJ, 29:138-39. Transcription available at Founders Online. See Jefferson, "A Memoir on the Discovery of Certain Bones of a Quadruped of the Clawed Kind in the Western Parts of Virginia," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 4 (1799): 251. See also Jefferson's draft, Memoir on the Megalonyx, [February 10, 1797], in PTJ, 29:291-99. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ For an exhaustive account of the circumstances surrounding Jefferson's error and the presentation of his paper, see Julian P. Boyd, "The Megalonyx, the Megatherium, and Thomas Jefferson's Lapse of Memory," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 102 (October 1958): 420-35.

- ^ Dr. Caspar Wistar, "A Description of the Bones Deposited, by the President, in the Museum of the Society," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 4 (1799): 526-31.

- ^ Silvio A. Bedini, "Thomas Jefferson and American Vertebrate Paleontology," Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Publication 61 (Charlottesville: Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, 1985): 10.