"And when I meet Thomas Jefferson"

One of the emotional insights of the hit musical Hamilton is its portrayal of the passionate friendship between the protagonist and his brilliant, self-assured sister-in-law—Angelica Schuyler Church. What the show doesn't mention is that Church also pursued a long-term friendship with one of Alexander Hamilton's greatest political rivals—Thomas Jefferson. Among the complexities of politics in the late eighteenth century Atlantic world, plenty of such contradictory alignments came about. When Church and Jefferson met, in the winter of early 1788, it was as two Americans in Paris. The friendship they developed lasted through a decade of revolutionary tumult.

One of the emotional insights of the hit musical Hamilton is its portrayal of the passionate friendship between the protagonist and his brilliant, self-assured sister-in-law—Angelica Schuyler Church. What the show doesn't mention is that Church also pursued a long-term friendship with one of Alexander Hamilton's greatest political rivals—Thomas Jefferson. Among the complexities of politics in the late eighteenth century Atlantic world, plenty of such contradictory alignments came about. When Church and Jefferson met, in the winter of early 1788, it was as two Americans in Paris. The friendship they developed lasted through a decade of revolutionary tumult.

Curious readers have long wondered whether Church's feelings for Hamilton were more than sisterly, just as they have taken similar interest in Jefferson's relationship with Maria Cosway. In fact, Cosway and Church were firm friends before the latter even met Jefferson. “If I did not love her so much I should fear her rivalship,” Cosway wrote Jefferson on Christmas day, 1787. “But no, I give you free permission to love her with all your heart.” The same flirtatious style quickly emerged in letters between Jefferson and Church. “The morning you left us, all was wrong,” he wrote her in February, “even the sunshine was provoking, with which I never quarrelled before.” Had Church, as Cosway predicted, really become “reigning Queen” of Jefferson's heart?

The answer is, not really. As Cassandra Good's recent, prize-winning book Founding Friendships carefully explains, Jefferson's gallant and sentimental style was a fashionable way for men and women to write to each other in the eighteenth century, perfectly acceptable in a platonic friendship. For Church and Jefferson, moreover, a shared love of Laurence Stern's novels—which acutely skewered genteel affectations of sensibility—gave a satirical edge to their correspondence. Church's letters to him were marked by a coy, knowing self-consciousness. “I hope that you will sometimes think of me with affection, because I wish it,” she wrote to him. “Is that a good reason?”

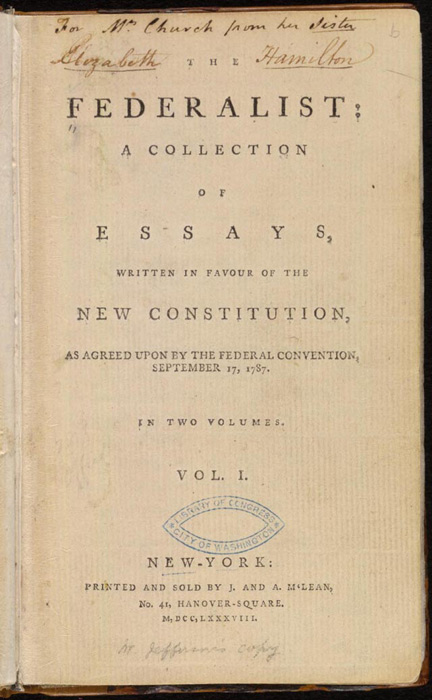

Jefferson and Church's correspondence was equally complicated and ironic when it came to politics. “You see by the papers, and I suppose by your letters also, how much your native state has been agitated by the question on the new Constitution,” wrote Jefferson in September 1788. Indeed, in spite of all Hamilton's efforts, ratification was a hard-won battle in New York, where Governor George Clinton was a leading antifederalist. “But that need not agitate you,” Jefferson went on. “The tender breasts of ladies were not formed for political convulsion.” Surely, he was at least half joking? Jefferson was certainly not ready to see women playing a full role in politics. But he knew women like Angelica Church were just as committed as he was to the revolutionary cause.

Jefferson and Church's correspondence was equally complicated and ironic when it came to politics. “You see by the papers, and I suppose by your letters also, how much your native state has been agitated by the question on the new Constitution,” wrote Jefferson in September 1788. Indeed, in spite of all Hamilton's efforts, ratification was a hard-won battle in New York, where Governor George Clinton was a leading antifederalist. “But that need not agitate you,” Jefferson went on. “The tender breasts of ladies were not formed for political convulsion.” Surely, he was at least half joking? Jefferson was certainly not ready to see women playing a full role in politics. But he knew women like Angelica Church were just as committed as he was to the revolutionary cause.

Indeed, Church was involved in her fair share of political intrigues. Among them was the quixotic attempt, in 1794, to free the Marquis de Lafayette from his imprisonment in the Austrian fortress of Olmutz. Church helped fund and organise the plot, along with a coterie of French émigrés in London (the adventure is detailed in Paul Spaulding's book Lafayette: Prisoner of State). As the French Revolution and its political impact developed on both sides of the Atlantic, American politics too became increasingly polarised. By the mid-1790s, Church found her friend Jefferson and her brother-in-law Hamilton implacably opposed to one another. Yet she maintained the correspondence with Jefferson, who continued to wish for her return to the United States.

That moment finally came in 1797, in the midst of a transatlantic financial crisis caused by the British government's mounting expenses from the war with France. To Jefferson, Church's return to New York underscored the superiority of the New World to the Old. “I feel one anxiety the less for the fate of the rotten bark [that is, Europe!] from which you have escaped,” he wrote her. Still, all was not altogether well in America either. “I wish I could have welcomed you to a state of perfect calm: but you will find that the agitations of Europe have reached even us.”

As Federalist and Republican partisanship reached new heights under President John Adams, Jefferson strained to find in his friendship with Church a way to sooth the pain of political division:

As Federalist and Republican partisanship reached new heights under President John Adams, Jefferson strained to find in his friendship with Church a way to sooth the pain of political division:

"We have not yet learnt to give every thing to it’s proper place, discord to our senates, love and friendship to society. Your affections, I am persuaded, will spread themselves over the whole family of the good, without enquiring by what hard names they are politically called. You will preserve, from temper and inclination, the happy privilege of the ladies, to leave to the rougher sex, and to the newspapers, their party squabbles and reproaches."

Was Jefferson serious this time? Did he see, in hardening gender roles and more firmly separated spheres, a solution to—or at least, a respite from—the problem of political polarisation? As Rosemary Zagarri has shown, the end of the eighteenth-century and the beginning of the nineteenth saw a renewed effort to exclude women from political activity. Attitudes like the one in Jefferson's letter held that women were good for friendship and sentiment, but not for arguments or ideas. If that was what he really thought, it did little justice to his friend Angelica Church. As any fan of Hamilton knows, she was not one to put her tender heart before her head.

Tom Cutterham began his research on Angelica Schuyler Church as a Fellow at the Robert H. Smith Internal Center for Jefferson Studies in summer 2014. Tom holds a DPhil from St. Hugh’s College, Oxford and currently teaches colonial North American and United States history at New College, Oxford. He is writing a biography of Angelica, which will explore the worlds of high society, finance, and politics in the midst of transatlantic revolutions. His blog for the Monticello website gives us a preview of this project, exploring the delicate dynamics of maintaining friendships with two legendary political opponents, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson.