Declaration of Independence Printings and Engravings

Jefferson kept the rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, "scored and scratched like a schoolboy's exercise," at Monticello all his life.[1] He counted his authorship of what he called "an expression of the [A]merican mind" first among the achievements for which he wished to be remembered.[2] An engraving of John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence hung in Monticello's Entrance Hall.

One visitor reported that Jefferson used the print to illustrate a discussion of the historic event.[3] He also owned at least three different prints of the document itself. All three were published more than forty years after the original, during a time of fierce nationalism following the War of 1812.[4]

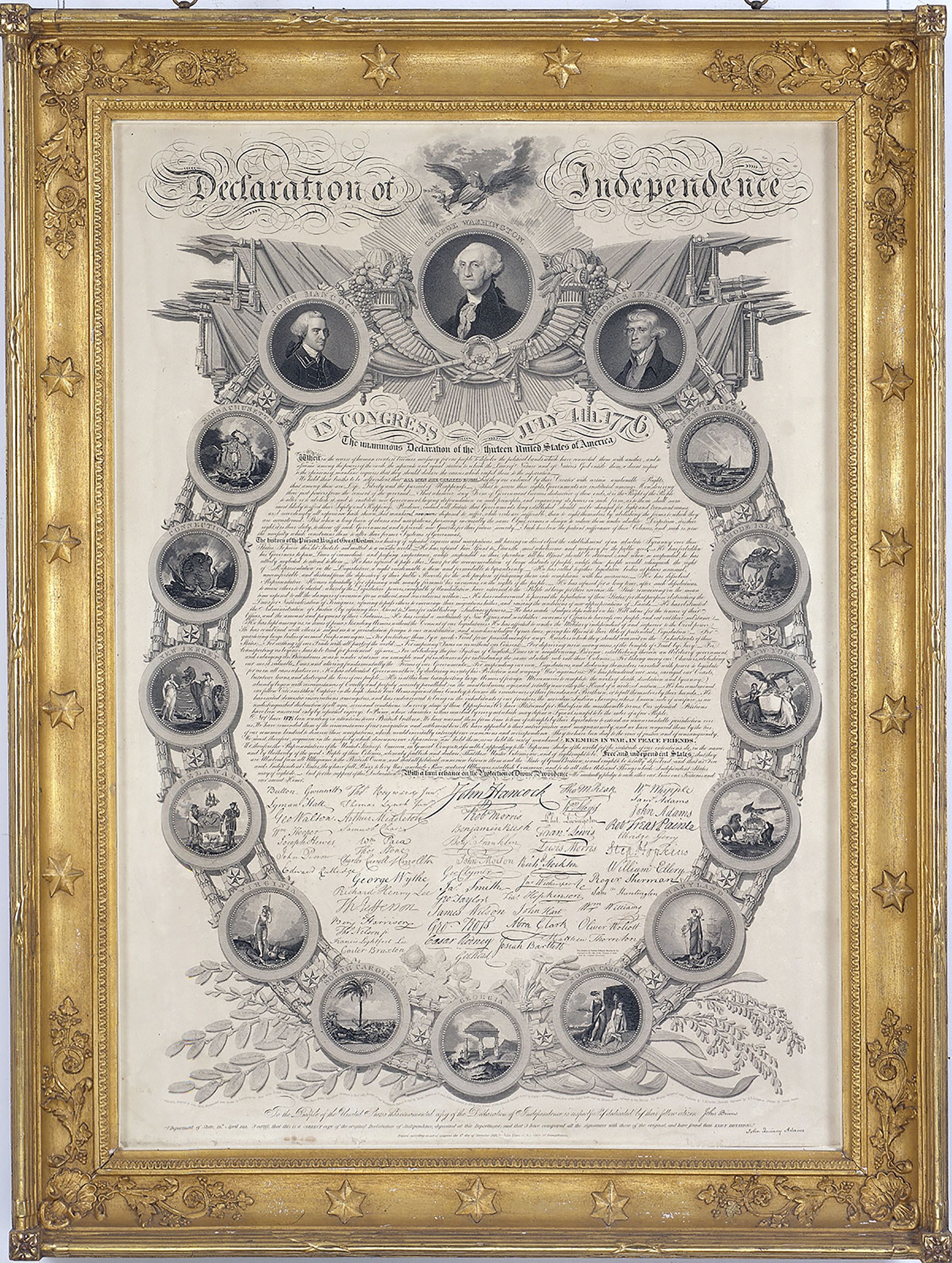

Although the first published copy of the Declaration was made on the evening of July 4, 1776, by the Philadelphian John Dunlap, it was not until 1818 that Americans could see the text in engraved writing as opposed to print. A virtual war ensued between rival printers John Binns and Benjamin Owen Tyler to be the first to publish and garner Jefferson's endorsement.[5] Binns was the publisher of the Republican Philadelphia newspaper The Democratic Press. In June 1816, he began taking subscriptions for his print of the Declaration, which was to be surrounded by portraits of John Hancock, George Washington, and Jefferson, and the seals of all thirteen states, but he failed to produce the work until 1819.

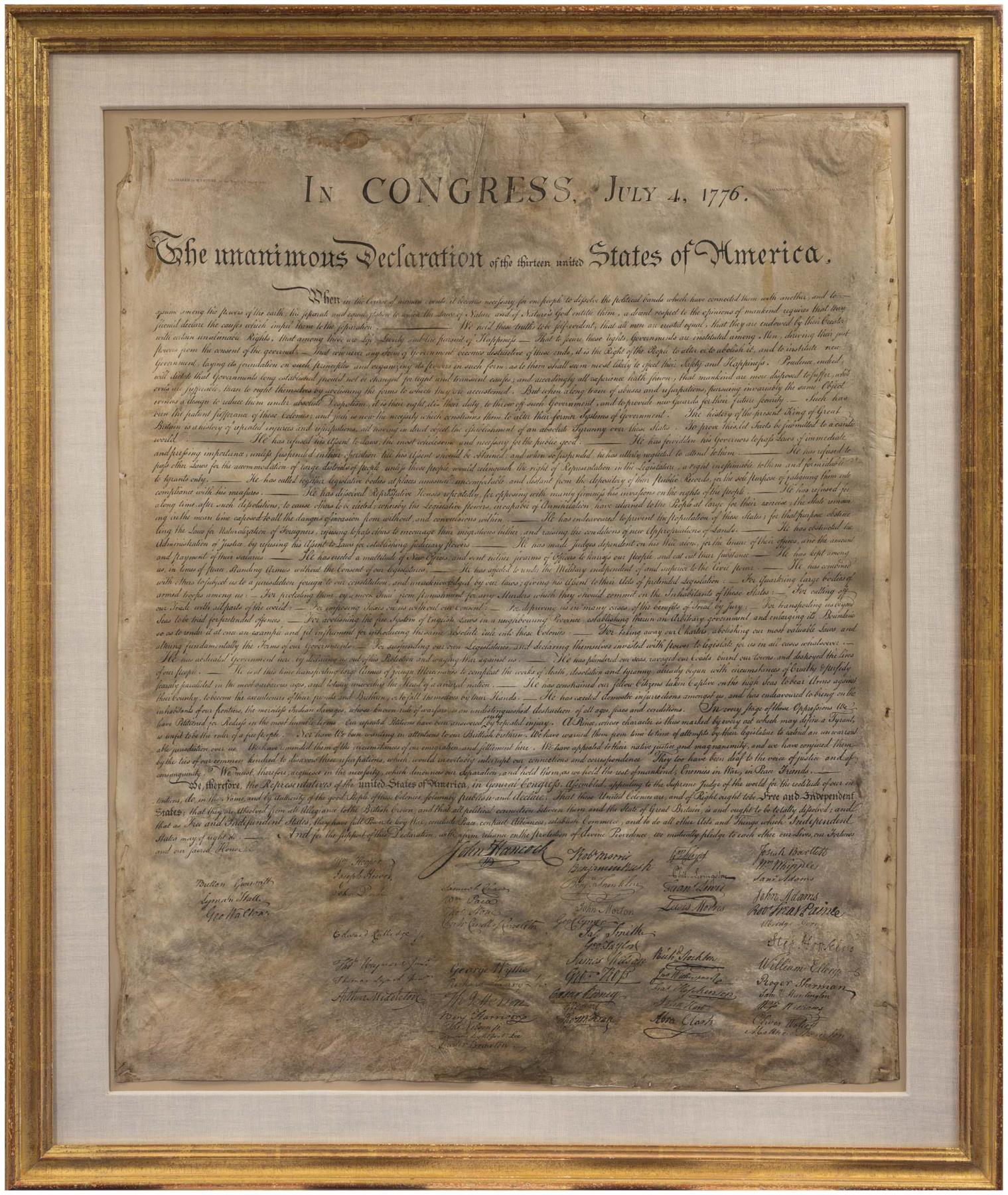

In the meantime Tyler took advantage of Binns's publicity and produced a less expensive and unornamented print in April 1818, complete with facsimile signatures and a dedication to Jefferson. Tyler was a self-taught calligrapher and penmanship instructor. [fn]Bidwell, "American History in Image and Text," 250-54.

Tyler gave credit for his plan of reproducing the Declaration of Independence to William P. Gardner, who had corresponded with Jefferson in 1813 about the idea. See Noble E. Cunningham, Popular Images of the Presidency from Washington to Lincoln (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1991), 91-94.[/fn] When he asked Jefferson for permission to dedicate the engraving to him, Jefferson consented but reminded Tyler that he was "but a fellow-laborer" with the other signers:

for the few of us remaining can vouch, I am sure, on behalf of those who have gone before us, that notwithstanding the lowering aspect of the day, no hand trembled on affixing it's signature to that paper.[6]

Tyler sent Jefferson a copy of his work on parchment, and sometime after May 1818, paid a visit to Monticello, where he spent the day teaching penmanship to Jefferson's family.[7]

Binns's response to Tyler's success was to dedicate his work to the people of the United States. He sent a proof of the print to Jefferson in 1819 soliciting comments. "[T]he dedication to the people is peculiarly appropriate," Jefferson wrote, "for it is their work, and particularly entitled to my approbation with whom it has ever been a principle to consider individuals as nothing in the scale of the nation." Jefferson added that the print's "great value will be in it's exactness as a fac-simile to the original paper," a comment that foreshadowed Binns's next struggle.[8]

Binns had hoped to sell 200 copies of his print to the government but was disappointed in 1820 by then secretary of state John Quincy Adams's commission of an exact facsimile of the original by William J. Stone. When completed in 1823 Stone's print was considered the "official" copy for government use; two copies were sent to each of the three remaining signers, Jefferson, John Adams, and Charles Carroll, as well as the marquis de Lafayette.

Other copies were distributed to governors and presidents of colleges and universities.[9]

Jefferson's prints of the Declaration were dispersed among his family following his death in 1826, and none are known to survive today.

- Text from Stein, Worlds, 1993

Further Sources

- Library of Virginia. "Virginia Memory: This Day in Virginia History."

- Wikipedia Commons. "Image of Stone's Declaration of Independence (1823)."

References

- ^ The description comes from an unidentified visitor's account to Monticello, cited in Dumas Malone, The Story of the Declaration of Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 72.

- ^ See Jefferson to Henry Lee, May 8, 1825, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress (transcription available at Founders Online); see also Design for Tombstone and Inscription [before July 4, 1826], Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress (transcription available at Founders Online).

- ^ Rev. Henry C. Thweatt, D.D., notes on visit to Monticello before 1825, private collection. For a discussion of the competition between Trumbull, Binns, and Tyler, see John Bidwell, "American History in Image and Text," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society vol. 98, pt. 2 (1989): 249, 257.

- ^ Malone, Declaration of Independence, 72, 79-80, 248, 253.

- ^ Bidwell, "American History in Image and Text," 247-303.

- ^ Jefferson to Tyler, March 26, 1818, in PTJ:RS, 12:557-58. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Martha Jefferson Randolph to Jane Nicholas Randolph, n.d. [c. 1818-1826], Nicholas P. Trist Papers, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- ^ Jefferson to Binns, August 31, 1819, in PTJ:RS, 14:644. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ For an exhaustive examination of the distribution of copies, see William R. Coleman, "Counting the Stones – A Census of the Stone Facsimiles of the Declaration of Independence," Manuscripts vol. 42, no. 2 (Spring 1991): 97-105.