Over the past two weeks, the archaeology field crew, led by Field Research Manager Crystal Ptacek, has made exciting discoveries in the South Pavilion and the adjacent South Wing that connects the Pavilion to the mansion. They have unearthed evidence that will advance our understanding of the changing design and use of these spaces and inform our new restoration and interpretation initiatives. The excavations are part of the Mountaintop Project, a multi-year effort dedicated to revealing Jefferson’s Monticello and the enslaved and free people who lived and worked there.

Over the past two weeks, the archaeology field crew, led by Field Research Manager Crystal Ptacek, has made exciting discoveries in the South Pavilion and the adjacent South Wing that connects the Pavilion to the mansion. They have unearthed evidence that will advance our understanding of the changing design and use of these spaces and inform our new restoration and interpretation initiatives. The excavations are part of the Mountaintop Project, a multi-year effort dedicated to revealing Jefferson’s Monticello and the enslaved and free people who lived and worked there.

The South Pavilion, completed in 1770, is the oldest standing structure on the Mountaintop. It housed the original kitchen on the ground floor and served as Jefferson’s living quarters on the top floor. When Jefferson's enslaved and free workmen completed construction of South Wing around 1809, they filled the ground-floor room with three feet of dirt so that the new floor level matched the level in the Wing. The South Wing served to house domestic and work spaces previously located along Mulberry Row. The ground-floor room in the Pavilion became a wash house. We aimed to understand these construction efforts and discern what, if any, archaeological remains had survived an initial round of restoration in the 1940s and two rounds of visitor restroom construction.

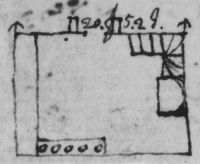

Despite Jefferson’s sketches and writings, the layout of the South Pavilion Kitchen is uncertain. One of Jefferson’s earliest sketches for the Kitchen included stew stoves and a dresser (Figure 1). Stew stoves were the 18th-century equivalent of cooktops. They were found only in the kitchens of people with economic means, social ambition, and skilled cooks needed to prepare meals influenced by in the French fashion. Kitchen dressers were sideboards or tables on which food was prepared. Jefferson also drew a central fireplace and stairs in the corner opposite of the stew stoves. While archaeologists consider historical documents, we do not rely on them. Jefferson often drew versions of his architectural ideas but never put them into practice. Thus, archaeology is uniquely positioned to confirm whether the stew stoves and dresser were installed and whether a central fireplace and stairs existed.

Despite Jefferson’s sketches and writings, the layout of the South Pavilion Kitchen is uncertain. One of Jefferson’s earliest sketches for the Kitchen included stew stoves and a dresser (Figure 1). Stew stoves were the 18th-century equivalent of cooktops. They were found only in the kitchens of people with economic means, social ambition, and skilled cooks needed to prepare meals influenced by in the French fashion. Kitchen dressers were sideboards or tables on which food was prepared. Jefferson also drew a central fireplace and stairs in the corner opposite of the stew stoves. While archaeologists consider historical documents, we do not rely on them. Jefferson often drew versions of his architectural ideas but never put them into practice. Thus, archaeology is uniquely positioned to confirm whether the stew stoves and dresser were installed and whether a central fireplace and stairs existed.

Our initial excavation strategy was to dig a row of five-foot quadrats across the north wall of the Pavilion to expose the original kitchen floor. We removed the modern tile floor and poured concrete subfloor of the restroom, then the fill in a series of trenches for pipes that served the restroom, then the brick and concrete subfloor that restoration architect Milton Grigg had installed in the 1940s as part of a first restoration of the space, then the fill in a large hole that Grigg had dug in the northwest corner in search of the original floor, and finally the dirt that Jefferson’s workmen had dumped into the Kitchen in 1809 (Figure 2).

Our initial excavation strategy was to dig a row of five-foot quadrats across the north wall of the Pavilion to expose the original kitchen floor. We removed the modern tile floor and poured concrete subfloor of the restroom, then the fill in a series of trenches for pipes that served the restroom, then the brick and concrete subfloor that restoration architect Milton Grigg had installed in the 1940s as part of a first restoration of the space, then the fill in a large hole that Grigg had dug in the northwest corner in search of the original floor, and finally the dirt that Jefferson’s workmen had dumped into the Kitchen in 1809 (Figure 2).

We found a diverse mixture of 18th- and 19th-century artifacts in Grigg’s backfill include sherds of Chinese porcelain, rusticated canaryware, blue shell edge pearlware, yellowware, ironstone, Jackfield-type, and creamware; bone, shell, Prosser, and copper alloy buttons; green wine bottle glass; handmade brick; mortar; window glass; straight pins; a thimble; nails; beads; two bone toothbrush heads; and a slate pencil (Figures 3-5). The presence of gastroliths, small stones or pieces of ceramics swallowed by chickens to aid digestion, and large amounts of faunal material suggest Grigg brought sediment into the Pavilion from the Kitchen Yard. However, fewer artifacts are found in sediment not disturbed by Grigg’s excavations, indicating this fill came from the excavation of the South Wing which raised the ground level three feet.

We found a diverse mixture of 18th- and 19th-century artifacts in Grigg’s backfill include sherds of Chinese porcelain, rusticated canaryware, blue shell edge pearlware, yellowware, ironstone, Jackfield-type, and creamware; bone, shell, Prosser, and copper alloy buttons; green wine bottle glass; handmade brick; mortar; window glass; straight pins; a thimble; nails; beads; two bone toothbrush heads; and a slate pencil (Figures 3-5). The presence of gastroliths, small stones or pieces of ceramics swallowed by chickens to aid digestion, and large amounts of faunal material suggest Grigg brought sediment into the Pavilion from the Kitchen Yard. However, fewer artifacts are found in sediment not disturbed by Grigg’s excavations, indicating this fill came from the excavation of the South Wing which raised the ground level three feet.

Despite the modern pipe-trench intrusions,  we located the remains of a fireplace in the northwest corner of the room by finding several important architectural features. Gaps in the brick wall, called racking, indicate where the chimney keyed into the wall of the Pavilion, and an angled brick shows where the arch of the fireplace rested. We also found ash, charcoal, and burned bricks in the back of the fireplace, evidence of some of the last fires that burned in the space. We discovered iron gudgeons, anchors for the iron crane from which pots would have been suspended over the fireplace, still attached to the wall of the Pavilion (Figure 6). Lastly, we found the original brick floor of the Kitchen, which is black from charcoal and 40 years of use.

we located the remains of a fireplace in the northwest corner of the room by finding several important architectural features. Gaps in the brick wall, called racking, indicate where the chimney keyed into the wall of the Pavilion, and an angled brick shows where the arch of the fireplace rested. We also found ash, charcoal, and burned bricks in the back of the fireplace, evidence of some of the last fires that burned in the space. We discovered iron gudgeons, anchors for the iron crane from which pots would have been suspended over the fireplace, still attached to the wall of the Pavilion (Figure 6). Lastly, we found the original brick floor of the Kitchen, which is black from charcoal and 40 years of use.

Along the northern wall of the South Pavilion, we found remains of the stew stoves in the location that Jefferson sketched (Figures 7-10). Stew stoves were about waist-high, made of brick, and had a grate onto which a cook would put hot coals. On top of the grate was space for an iron trivet, which would hold a pot. While it is unclear exactly what year he installed the stoves at Monticello, Jefferson may have seen them while he was traveling abroad in France in the 1780s as well as in the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, Virginia, in the 1760s and 70s. This find is particularly exciting because these stoves represent some of the earliest stew stoves in British North America! We also confirmed that this corner is where the dresser attached to the wall. We found gaps in the plaster and slats in the brickwork where shelves connected to the wall.

Along the northern wall of the South Pavilion, we found remains of the stew stoves in the location that Jefferson sketched (Figures 7-10). Stew stoves were about waist-high, made of brick, and had a grate onto which a cook would put hot coals. On top of the grate was space for an iron trivet, which would hold a pot. While it is unclear exactly what year he installed the stoves at Monticello, Jefferson may have seen them while he was traveling abroad in France in the 1780s as well as in the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, Virginia, in the 1760s and 70s. This find is particularly exciting because these stoves represent some of the earliest stew stoves in British North America! We also confirmed that this corner is where the dresser attached to the wall. We found gaps in the plaster and slats in the brickwork where shelves connected to the wall.

The construction of the South Wing in 1808 resulted in important changes to the South Pavilion. A Wash Room replaced the Kitchen when it was moved to the newly built South Wing and the first floor of the South Pavilion was buried with three feet of fill. The original Pavilion door along the south wall was converted into a window, and the door moved to the east wall. A large window that opened to the new Dairy in the South Wing was bricked up to the left of the door. The fireplace in the northwest corner was removed and then buried, replaced by a central fireplace which served to heat kettles of water for the Wash Room.

The construction of the South Wing in 1808 resulted in important changes to the South Pavilion. A Wash Room replaced the Kitchen when it was moved to the newly built South Wing and the first floor of the South Pavilion was buried with three feet of fill. The original Pavilion door along the south wall was converted into a window, and the door moved to the east wall. A large window that opened to the new Dairy in the South Wing was bricked up to the left of the door. The fireplace in the northwest corner was removed and then buried, replaced by a central fireplace which served to heat kettles of water for the Wash Room.

Our archaeological work extended into the South Wing, where we investigated the space occupied by a dairy and two heated rooms occupied by enslaved domestic servants. Jefferson's grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph told 19th-century biographer Henry Randall that one of the rooms was home to Sally Hemings. We sought to find evidence of room partitions, dairying equipment, or subfloor pits. Unfortunately, excavations revealed that, with a couple of exceptions, any Jefferson-period features were destroyed by the installation of the men’s and women’s restrooms in the 1940s and 1960s. However, we found one of the original fireplace hearths in one of the heated rooms (Figure 12), along with a single row of bricks for the original floor.

Our archaeological work extended into the South Wing, where we investigated the space occupied by a dairy and two heated rooms occupied by enslaved domestic servants. Jefferson's grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph told 19th-century biographer Henry Randall that one of the rooms was home to Sally Hemings. We sought to find evidence of room partitions, dairying equipment, or subfloor pits. Unfortunately, excavations revealed that, with a couple of exceptions, any Jefferson-period features were destroyed by the installation of the men’s and women’s restrooms in the 1940s and 1960s. However, we found one of the original fireplace hearths in one of the heated rooms (Figure 12), along with a single row of bricks for the original floor.

The most interesting architectural feature we discovered in the South Wing was a portion of a flight of stairs from the 1770s (Figure 13). These stairs were originally located outside of the South Pavilion and led from the Kitchen on the first level of the Pavilion up to the West Lawn. When Jefferson moved to Monticello in 1770, he occupied the upper room of the Pavilion, which was a free-standing building. The lower level was finished as a kitchen.

The most interesting architectural feature we discovered in the South Wing was a portion of a flight of stairs from the 1770s (Figure 13). These stairs were originally located outside of the South Pavilion and led from the Kitchen on the first level of the Pavilion up to the West Lawn. When Jefferson moved to Monticello in 1770, he occupied the upper room of the Pavilion, which was a free-standing building. The lower level was finished as a kitchen.

After Jefferson moved out of the South Pavilion to the main house around 1778, the Pavilion still functioned as the kitchen, and the enslaved cooks used these steps to access the West Lawn and bring prepared food to the main house dining room. While pipes from the 1940s and 1960s intrude, many steps were found in-situ and appear to continue down to the level of the original kitchen floor. The staircase is an important architectural trace of the first Monticello.

Stay tuned as the archaeology field and lab teams work together over the coming months to catalog and analyze the thousands of artifacts recovered in the excavations. You can follow our work on our “Archaeology at Monticello” Facebook page.

—This post was written by Crystal Ptacek and Bea Arendt

The Mountaintop Project is made possible by a transformational contribution from David M. Rubenstein. Leading support was provided by Fritz and Claudine Kundrun, along with generous gifts and grants from the Sarah and Ross Perot, Jr. Foundation, the Robert H. Smith Family Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. John H. Birdsall, Mr. and Mrs. B. Grady Durham, the Mars Family, the Goode Family Foundation, the Richard S. Reynolds Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, Charlotte Moss and Barry Friedberg, Christopher J. Toomey, Sally and Joe Gladden, the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, the Mary Morton Parsons Foundation, the Cabell Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. Richard A. Mayo, the Manning Family Foundation, Jan Karon, the Garden Club of Virginia, and additional individuals, organizations, and foundations.

ADDRESS:

1050 Monticello Loop

Charlottesville, VA 22902

GENERAL INFORMATION:

(434) 984-9800