Tracking Down Jefferson's Correspondence

When Thomas Jefferson was seventy-four years old and had been retired from Washington for seven years, he mused in a letter to William Short on 5 May 1816 that “when the world imagines I have nothing to do, I am in a state of as heavy drudgery as any office of my life ever subjected me to. from sunrise till noon I am chained to the writing table.”

Not only was Jefferson busy writing to friends and acquaintances, but he very often responded to the unsolicited mail he received as well. Add to that his necessary correspondence related to financial transactions, book orders, tax payments, etc., etc., and the letters start to pile up. A lot. In the same 1816 letter to William Short, Jefferson explained that he was too busy writing correspondence to have time to write his memoirs, but that “the letters I have written while in public office are in fact memorials of the transactions with which I have been associated, and may at a future day furnish something to the historian.” We here at Monticello argue that his writings furnish a great deal to historians even after his retirement from public office.

At the Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series, we are working to produce the “definitive edition” of Jefferson’s writings and correspondence between his retirement from the presidency in 1809 and his death in 1826. That means we try to account for everything possible in his correspondence, both incoming and outgoing. One of the first things the editors of the Retirement Series did when the project began was they compiled a database of all of Jefferson’s letters. Considering how many letters there were, you might wonder how in the world we can account for all his mail now that two hundred years have passed.

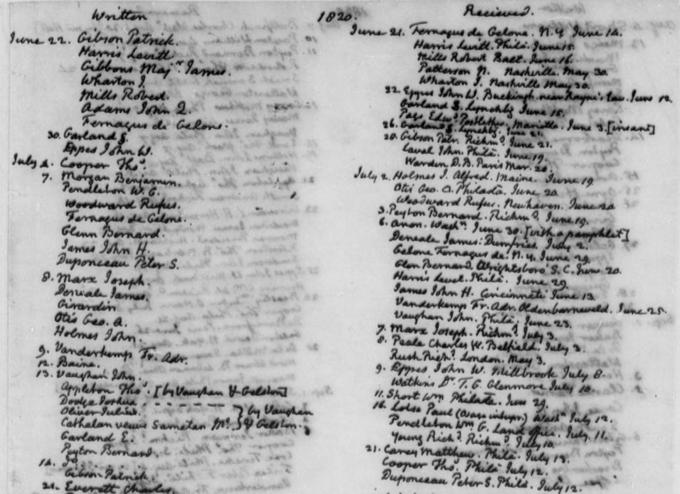

Luckily we have Mr. Jefferson helping us out. We all know he was a devoted record-keeper, and naturally that carried over into his papers. From late 1783 until shortly before his death, Jefferson maintained a “Summary Journal of Letters” (now located at the Library of Congress and accessible online here.) In this chronological journal he recorded all his “Written” letters on the left, and his “Recieved” letters on the right. The left column gives the name of the person Jefferson wrote to and is organized by the date written. The right column is organized by the date Jefferson received the letter, and includes the letter’s author, date written, and location from which it was sent. Occasionally he added other details, perhaps noting who delivered a letter if it was not sent through the mail, or making a comment about the sender. (Look at the letter received on 22 June from Edward P. Page and notice Jefferson’s bracketed notation “insane.”)

Using the Summary Journal of Letters, we not only know what Jefferson wrote and received, but we can compare it with our records to give us a much more accurate idea about which letters remain unfound or have not survived. Jefferson’s papers are scattered throughout dozens of archives and libraries across the country, (not to mention private homes and dealers), and we will never find every single piece of correspondence. But thanks to Jefferson’s help our job is made a little easier.