The Lasting Legacy of Marie Kimball

How do we know what Monticello looked like during Jefferson’s time? Monticello has been called one of the best-documented plantations, and the same goes for the house interior; we are lucky to have a wealth of correspondence, visitor accounts, and even diagrams from Jefferson’s time. Today, we take for granted all of these rich sources and records that help us in our work. But back in the early 20th century, the situation was far different. For Women’s History Month, it feels appropriate to honor Marie Kimball, the woman who first rediscovered these sources and helped to make Monticello what it is today.

1912 Monticello's Entrance Hall by Rufus Holsinger. Image courtesy Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

In 1923, when the Thomas Jefferson Foundation purchased Monticello, the house was in good repair thanks to the stewardship of Uriah and Jefferson Monroe Levy, but the interior looked far different than it had during Jefferson’s time. All of the people who had lived at Monticello during the late 18th and early 19th centuries were long dead, and the records they left had been sitting unexamined in family attics and archives. It wasn’t necessarily standard practice in the early 20th century to restore house museums accurately to their historic interior appearance; but for Marie Kimball and her husband Fiske, documents and historical research were key to their working methods. As it turned out, Marie Kimball was ideally suited for the task ahead of them.

Marie Goebel was born in 1889, the daughter of a German philology professor and a schoolteacher. She earned a college degree in 1911 from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, during a time when few women did so. Her father had a reputation for being rather abrasive professionally (famously getting fired from a job at Stanford), but was loving and supportive of his daughter and her academic pursuits; she assisted him with his research and published some early work under his supervision. During this time, she met and married a young architecture instructor named Sidney Fiske Kimball (despite Fiske reportedly getting thrown out of the Goebel house by Marie’s father for swearing).

Marie and Fiske Kimball. Image courtesy Fiske Kimball Papers, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives

Like many women of her time, Marie Kimball also assisted her husband in his academic projects. When a large cache of Thomas Jefferson's architectural drawings were donated by descendants of his granddaughter Ellen Coolidge to the Massachusetts Historical Society, Fiske Kimball was the first scholar since Jefferson's death to study them and recognize Jefferson's skill as an architect. But it was his wife Marie who did much of the legwork in sifting through Jefferson's correspondence for clues to his architectural work. She also, like any good academic, took the opportunity to spin her research out into multiple articles.

When the Thomas Jefferson Foundation acquired Monticello in 1923 with plans to restore and open it as a historic site, Fiske Kimball was eager to join the effort and was soon named the director of restoration. For the rest of his life, he held this position, in addition to being the director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art until shortly before his death. One might well ask how one man could hold what amounted to two full-time jobs, in addition to countless other projects; part of the answer was surely the help of his wife Marie, and predictably, she soon became involved in the restoration effort at Monticello as well. By this time, both Kimballs were deeply steeped in Jefferson’s world, so much so that they named a dog of theirs Jefferson (which makes for amusing reading as they’re describing the dog’s various misdeeds).

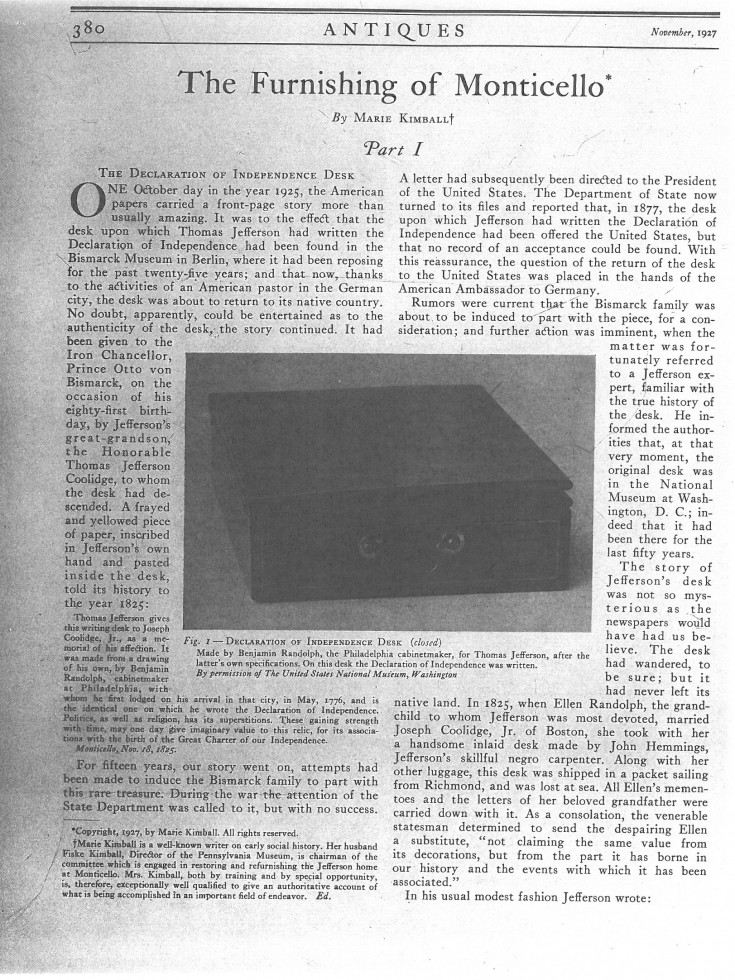

First page of "The Furnishings of Monticello" by Marie Kimball from the November 1927 edition of The Magazine Antiques

In 1927, Fiske Kimball wrote to the Board of Directors of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, “I sent Mrs. Kimball to Washington to look up various matters, in which she was very successful.” The documents that Marie Kimball was “successful” in unearthing for the first time in decades are the ones that we know so well now, and use almost daily in our work. They included Jefferson’s account books – “those candid tattlers of his every act,” as Marie later described them; accounts of visitors to Monticello; and a list of paintings that hung in Monticello, among other materials. Based on the results of this research trip, she published a landmark two-part article later that year in The Magazine Antiques, “The Furnishing of Monticello.”

Later edition of Thomas Jefferson's Cook Book by Marie Kimball

Marie Kimball continued to assist with the restoration of Monticello, in addition to publishing dozens of books and articles on various Jeffersonian topics, for the rest of her life. Perhaps her most well-known contribution was Thomas Jefferson’s Cook Book (1938), which went through eight editions until it was finally superseded in 2005 by Dining at Monticello; she also completed three volumes in a multi-volume biography of Jefferson. She was named the first curator of Monticello in 1944, in recognition of the work she had been doing for so long. She was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1945, and, in 1949, she became the first woman invited to give the Founder’s Day address at the University of Virginia. Always her biggest cheerleader, her husband once wrote proudly to her publisher, “You can scarcely realize the vast amount of new documentary material which makes what she has just sent you not merely new, but revolutionary in the conception of a man who has been presented as a pioneer frontiersman…That is new stuff, and hot stuff. If it can be properly brought out we will settle for the Pulitzer Prize in biography.” When she died suddenly in 1955, her husband lived only a few months longer without her.

The museum that Monticello is today is part of the legacy of this remarkable woman.