Life at Four Miles an Hour - Thomas Jefferson's World of the Horse

Imagine a world where life moved at four miles an hour, and the most one could readily travel in a day was just thirty miles. Such was the slow world Thomas Jefferson was born into in 1742. Although transportation via Virginia’s waterways was common, especially in the Tidewater area, most people traveled by foot or horse between plantations and towns. Roads were few and those that did exist were often impassable for carriage or wagon due to weather and mud. So horseback was generally the preferred, and sometimes only, way of long distance travel. Horses were part of the daily life of most people whether for travel, work or entertainment. The Reverend Hugh Jones, a teacher at the College of William and Mary, describing the place of horses in the eighteenth century, commented that Virginians “are such Lovers of Riding, that almost every ordinary Person keeps a Horse.” [1] Jefferson, like other young men of that time, place and social station, grew up on horseback, and was an excellent horseman. Throughout his life, horses held a special place in Jefferson’s heart.

Horses in Colonial Virginia

In 1609, the first Virginia horses arrived in Jamestown, but unfortunately did not survive the winter. At this time, as far as is known, none of the Native Americans in the Tidewater Virginia area owned or used horses. In 1611 Jamestown settlers were pleased when another shipment of seventeen horses arrived. Offspring of these small Irish and Scottish breeds eventually were crossbred with descendants of the Spanish horses from Florida producing a small sized horse breed good for both riding and farm work.

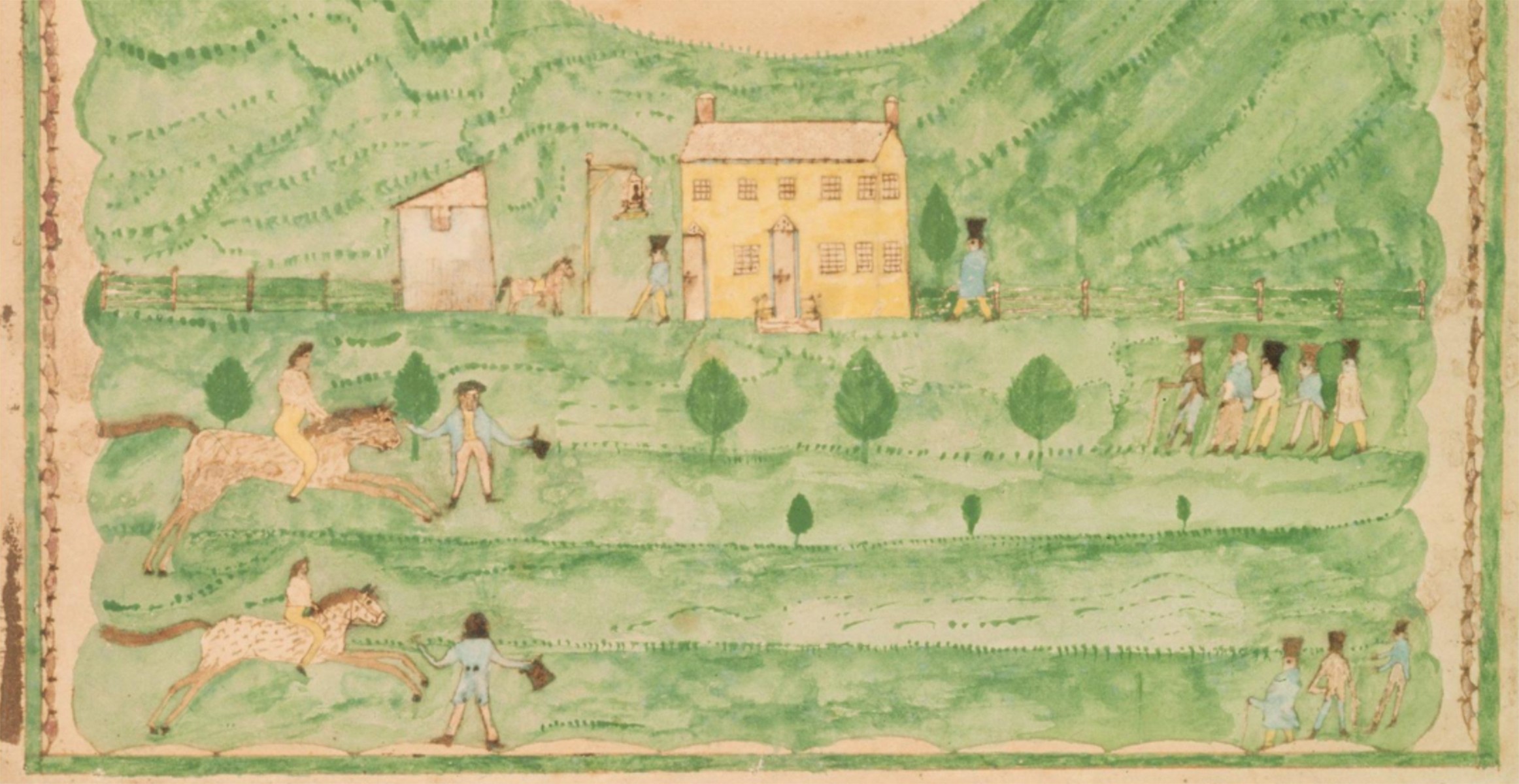

Lewis Miller, an artist, depicted himself and his brother on a ride through the Virginia countryside.[2]

The resulting horses were “the admirable little Virginia horse…”[3] They were hardy, low maintenance, could withstand the cold winters and would forage for their own food. And they were extremely fast for a short distance. They were known as Virginia Chickasaw horses.

Virginia planters loved racing. In the 1600’s only gentlemen – white men with land and means – could race their own horses. Quarter racing, a one-quarter mile race down a main street or a path through the woods on the little Chickasaw horses, became a popular sport for owners and spectators alike.

Depiction of a quarter race, ca. 1830(detail from "Birth Record for Samual Asay," Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

By 1700, there were race tracks throughout the more populated areas of Virginia, with most of the jockeys then being enslaved men and boys. When not racing, these horses were work animals pulling carriages and wagons or serving as riding stock. However, the Virginia race scene was about to undergo a great change.

Between 1690 and 1730, three outstanding stallions were imported to England to become the progenitors of the Thoroughbred breed, or “blooded” and high-born horses as they were called in Jefferson’s day. All modern Thoroughbreds descend from one of these three – the Byerly Turk, the Darnley Arabian and the Godolphin Arabian. Their offspring and descendants produced a new kind of racehorse – taller, stronger, faster and aesthetically more pleasing. And these descendants were brought to the colonies where they became very popular. Although Jefferson never participated in racing as an owner, he did enjoy viewing races and owning these beautiful animals. Many of Jefferson’s favorite riding horses descended from the Godolphin Arabian and had raced before Jefferson purchased them as riding and carriage horses.

Course races pitted several horses and their jockeys against each other on a mile-long oval track (detail from "A Race Meeting at Jacksonville, Alabama, by W.S. Hedges, Birmingham Museum of Art)

From Allycroker to Eagle – Jefferson’s Horses

Between 1761 and 1826, Jefferson owned over 100 horses. Of these, the majority were unnamed Chickasaw type horses used for farm work on the plantations ploughing fields and pulling wagons. The other 50 or so horses were “blooded” named riding and carriage horses, as well as broodmares and their offspring. For these horses, Jefferson recorded the age when obtained, pedigree, previous owner associations and price. Jefferson’s preference for his riding horses was a Bay stallion of about six years of age.[4]

The first riding horse of note was Allycroker, a high-bred bay mare that Jefferson inherited from his father-in-law, John Wayles, in 1774. Her foal, Caractacus, is probably the riding horse most mentioned by Jefferson’s visitors and most associated with Jefferson who owned the horse from his birth in 1775 until at least 1790. Caractacus was sired by Young Fearnought, a famed colonial stallion, who was a descendant of the Godolphin Arabian. Jefferson’s fine horses were not only for riding, but also trained to pull a carriage. In his retirement, the four horses that most often doubled as carriage horses were Diomede, Brimmer, Tecumseh, and Wellington. Edmund Bacon, the Monticello overseer during Jefferson’s retirement, wrote of the acquisition of these horses. Of Diomede he wrote that the horse was purchased by Jefferson’s son-in-law for 80 pounds in Chesterfield County. Bacon noted that the horse did not have a pleasant riding gait, but was a fine harness horse. Brimmer, an excellent riding and harness horse, was purchased in 1790. Tecumseh and Wellington were both purchased in 1815. Tecumseh was purchased from Davy Isaacs, a Charlottesville merchant who had connections with the descendants of the Monticello enslaved community. The story is that Jefferson saw the horse in the field in Charlottesville many times, and had Bacon inquire about purchasing the fine-looking horse. Bacon noted that Tecumseh was a tricky horse who easily shied, but that Jefferson had a “blind” made to attach to his harness when he rode or drove him which solved the problem. Jefferson’s last horse, and some say his favorite, was Eagle. Bacon recalled that the last thing he did for Jefferson before leaving Monticello was to purchase Eagle, which he describes as the finest sort of riding horse. He recalled receiving a letter in which Jefferson recounted that Eagle fell with him while crossing the river and that Jefferson re-injured his previously broken wrist.[5]

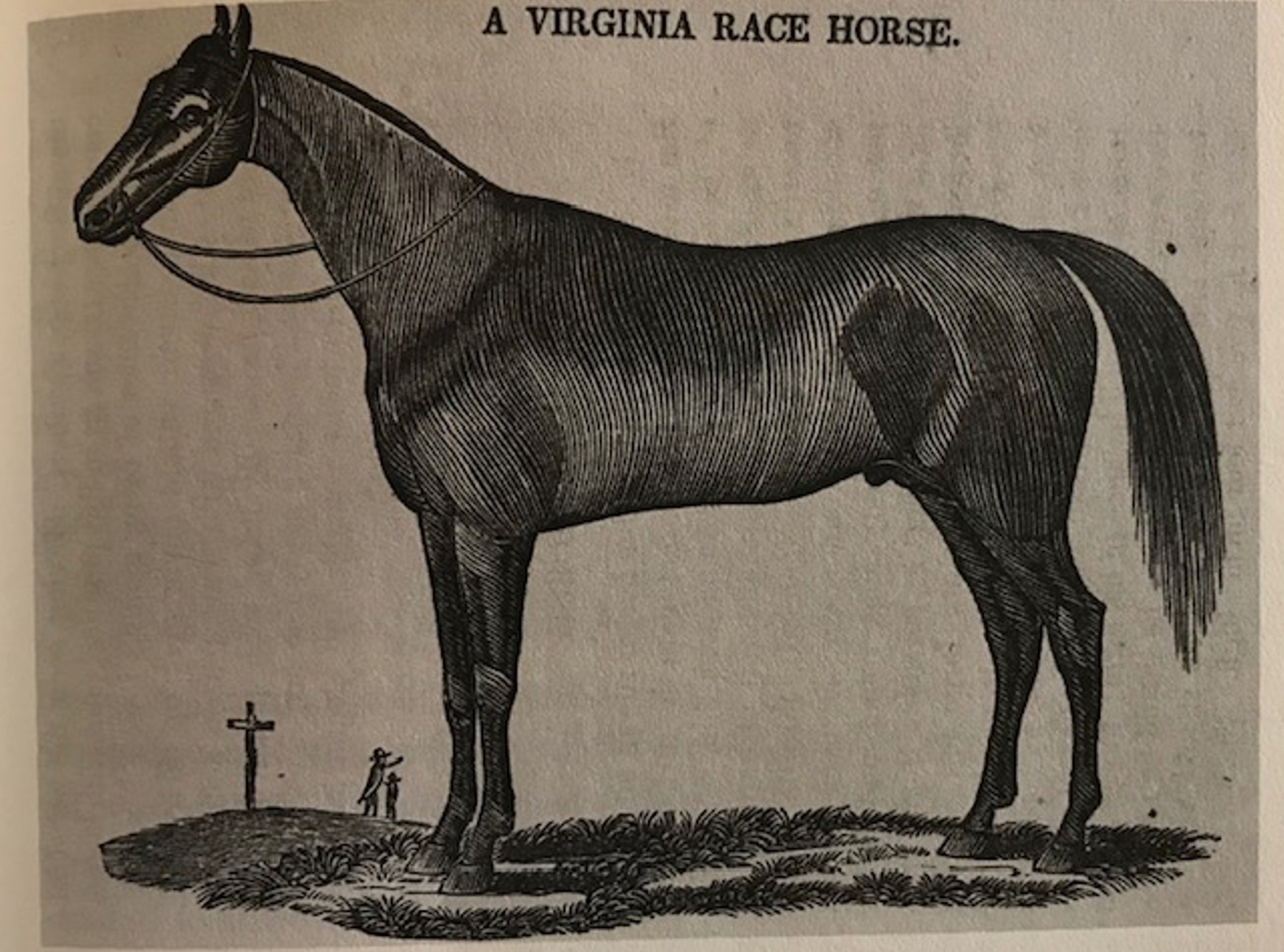

"A Virginia Racehorse” from The gentleman’s new pocket farrier

Vehicles Used at Monticello (and Mr. Jefferson, Please Let Me Out!)

There were a variety of vehicles used for transportation and pleasure at Monticello. Bacon stated that Jefferson generally liked to take the reins himself. During his retirement, Jefferson liked to drive a phaeton, which was a one- or two-horse open vehicle with one seat. A visitor, Margaret Bayard Smith, described a ride with Jefferson on the Monticello roundabout roads. “After breakfast, Mr J. sent E. (Jefferson’s granddaughter Ellen) to ask me if I would take a ride with him round the mountain; I willingly assented & in a little while I was summoned; the carriage was a kind of chair, which his own workmen had made under his direction, & it was with difficulty that he, Ellen & I found room in it, & might well be called thesociable.—The first circuit, the road was good, & I enjoyed the views it afforded & the familiar & easy conversation, which our sociable gave rise to; but when we descended to the second & third circuit, fear took from me the power of listening to him, or observing the scene; nor could I forbear expressing my alarm, as we went along a rough road which had only been laid out, & on driving over fallen trees & great rocks, which threaten’d an over set to our sociable & a roll down the mountain to us— “My dear madam,” said Mr J— “you are not to be affraid, or if you are you are not to show it; trust yourself implicitly to me, I will answer for your safety; I came every foot of this road yesterday, on purpose to see if a carriage could come safely, I know every step I take, so banish all fear.”—This I tried to do but in vain, till coming to a rock over which one wheel must pass I jumped out…”[6]

Overseer Bacon described one of the Monticello vehicles that Jefferson designed and had built when he returned after leaving the presidency. While the woodwork, blacksmithing and painting were done on the plantation by his enslaved workmen, (probably John Hemmings, Joe Fossett and Burwell Colbert), the plating was done in Richmond. When Jefferson traveled in this elegant carriage, Bacon noted he always used five horses. Four horses were used to pull the carriage and the fifth was for enslaved butler Burwell Colbert to ride behind. It was in this four-person Lansdowne carriage that Jefferson and his granddaughters would ride to his retreat plantation, Poplar Forest. At different times various other vehicles were also used. There was a cabriolet or two-wheel carriage, and an enclosed carriage called a chariot, as well as a two-wheel one-person vehicle called a sulky.

Live Q&A: Jefferson and Horses

Who Else Rode at Monticello?

Jefferson certainly was not the only person on horseback at Monticello. It is known that many of his enslaved workers also rode and would be sent on errands by horseback. Jupiter Evans, who was born at Shadwell plantation and grew up with Jefferson, would later become one of Jefferson’s “hostlers” who cared for the fine horses in Jefferson’s stable. Jefferson required immaculate cleanliness in the care of his fine horses. It was recalled that he would rub his white handkerchief across the horse when it was brought to him for his ride to determine if it had been well groomed. If any dust appeared on the handkerchief, he sent the horse back to the stable to be groomed again. Evans and his pride in caring for Jefferson’s horses is recounted in Lucia Stanton’s Those Who Labor for My Happiness. “Jefferson’s unruffled temper was legendary; his grandchildren could recall for a biographer only two instances of visible fury, one involving his coachman. After Jupiter twice refused to let a young slave sent by Jefferson take one of the carriage horses to the post office, he was summoned to the presence of his master, who was ‘evidently in a passion.’ Jupiter met with a look and tone ‘never before or afterwards witnessed at Monticello,’ but he ‘firmly declared that he must not be expected to keep the carriage horses in the desired condition, if they were to be ‘ridden round by boys.’”[7] It was recorded that in the end, Jefferson agreed with Jupiter Evans although the slave was told never to speak in that way to Jefferson again.

Jupiter Evans and later James Hemings or Burwell Colbert would accompany Jefferson on journeys riding on horseback behind the carriage that Jefferson was driving. At other times, enslaved workers James and Israel Gillette would ride postilion on one of the four horses pulling a carriage, guiding the horses from that position rather than utilizing a driver on the carriage.

Jefferson's Restored Phaeton

There were many other people also on horseback at the plantation. Jefferson’s sons-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph and John Wayles Eppes were often at Monticello and were noted as “good horsemen.” The Monticello overseers rode and often kept horses in their own stables. Edmund Bacon shared Jefferson’s interest in fine horses and breeding, and after leaving Monticello in 1822, moved to Kentucky where he was an important breeder for 40 years, probably using the knowledge acquired at Monticello. And, of course, guests showed up at Monticello, invited and not, by carriage and horseback. Bacon said there was room for 36 horses in the stables on the plantation, and these were many times filled. The women of Jefferson’s family were also accomplished riders. Women rode side-saddle for travel, leisure outings and fox hunting, as riding astride like men was considered unladylike. Jefferson’s wife, Martha, was mentioned as an excellent rider as was his daughter Martha. Granddaughter Cornelia must also have been a skilled horsewoman as Jefferson allowed her to ride his “fiery” stallion Eagle.[8]

Horses played a major role in Jefferson’s life. He had a lifelong passion for them and a powerful connection to them. Throughout his life, but especially after the early death of his wife in 1782, Jefferson enjoyed solitary rides not only at Monticello or Poplar Forest, but wherever he was living, including Washington and Paris. Contemporary accounts from Jefferson’s friends recall that Jefferson would ride along the trails and the seven miles of roundabout roads of Monticello for about three hours a day in all weathers.[9] Almost to the time of his death, Jefferson continued these rides. Just three weeks before he died at the age of 83 on July 4, 1826, Jefferson took a last ride around his beloved Monticello plantation on Eagle. Riding seemed to be a time of escape and solitude from the cares of his world, and a time to re-energize himself physically and mentally on a beloved horse.

Jefferson’s riding boots last worn three weeks before his death (Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello)

Jefferson’s riding boots last worn three weeks before his death (Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello)

FOOTNOTES

[1] Mackey-Smith, Colonial Quarter Race Horse, 11.

[2] Julie Campbell, The Horse in Virginia (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, , 2010), 14.

[3] Campbell, The Horse in Virginia, 17.

[5] Hamilton W. Pierson, The Private Life of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Charles Scribner, 1862), 56-58.

[6] “Margaret Bayard Smith’s Account of a Visit to Monticello, [29 July–2 August 1809],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-01-02-0315. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, vol. 1, 4 March 1809 to 15 November 1809, ed. J. Jefferson Looney. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004, pp. 386–401.]

[7] Lucia Stanton, “Those Who Labor for My Happiness”: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2012), 112.

[8] Douglass, “Jefferson and Horse Culture.”

[9] Douglass, “Jefferson and Horse Culture.”

This blog post was made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this program do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

This blog post was made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this program do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Installing animal silhouettes at Monticello's Stone Stables