How Rivalry Between Hamilton and Burr Influenced Election of 1800

Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull, 1792

In 1804 when Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr took to the "field of honor" to settle their differences, Burr killed Hamilton and simultaneously destroyed his political career forever. This duel was a tragic ‘end game’ to a fiercely contentious rivalry extending throughout their political lives, an opposition to each other that greatly influenced the outcome of the election of 1800!

How did this happen? First consider the politics of our early Republic. Although the U.S. Constitution did not provide for political parties in its framework, by John Adams’ election in 1796 two parties, the Federalists and the Republicans (or Democratic Republicans) had emerged with opposing ideas on the major issues of the day: such as relations with Great Britain and France, and our banking system and financial infrastructure. Each side believed they defended the true principles of the American Revolution and predicted the nation would fail if the other side won. Rival politicians attacked each other in party newspapers and private correspondence; character assassination and unfounded accusations were prevalent in a spirit of "venomous exuberance." The Burr/ Hamilton rivalry unfolded in the context of this turbulent era and was rooted in New York state politics.

Hamilton married the daughter of Phillip Schuyler, a Revolutionary War General and a powerful Federalist power broker in New York. Also a leading Federalist, Hamilton gained a reputation for using insults, slights and vicious letter-writing campaigns to attack anyone he believed stood in the way of achieving his political goals. He would employ all of these tactics against Burr.

Aaron Burr first became a target of Hamilton’s political animosity when he began to rise in state politics. Burr ran for a seat in the state assembly and won. In an age when candidates stood aloof from active campaigning so as not to appear too ambitious, Burr directly solicited votes from a more broadly based electorate of merchants and mechanics (urban workers). His unorthodox style was seen as a threat to the social order. Noah Webster criticized this new style of campaigning, saying it could make a "SOMEBODY" out of a "NOBODY." In 1791 Burr won a term as U.S. Senator, defeating Hamilton’s father-in-law, Schuyler, which further aroused Hamilton’s political enmity. Hamilton worked hard to diminish Burr’s influence. He argued Burr was "without principle," "malleable" in his views… not on board with the Federalists! Burr did not respond in kind; however resentment built, and he increasingly became a firm opponent of Hamilton.

Jefferson and Madison recognized Burr’s political savvy and ‘republican’ instincts. They sought him out on a trip to New York in 1792, intent on forging alliances in the North to create a national Republican party in opposition to the Federalists. In April of 1800 Burr engineered a brilliant campaign to win New York’s state legislature for the Republicans, which gave them all 12 of the state’s electoral votes. These would be cast for Jefferson and helped him win the Presidency. New York’s Federalists were stunned; Hamilton could not accept that power had slipped from their hands... and due to Burr, whose political success caused him to be tapped for the Republican ticket with Jefferson.

{As background, today the popular vote directly determines each state’s electoral vote for electors to the electoral college; in 1800 the method of choosing electors varied by state. Many were chosen by a vote of the state legislature. In addition, each elector had two votes to allocate, rather than our current system which allows one vote for President and one for Vice President. The person with the most votes became President, and the person in second became Vice President. To capture both offices, the Federalists and Republicans nominated two candidates. While Thomas Jefferson was intended as the Republican’s Presidential Candidate, both he and Aaron Burr were on the ballot for President.}

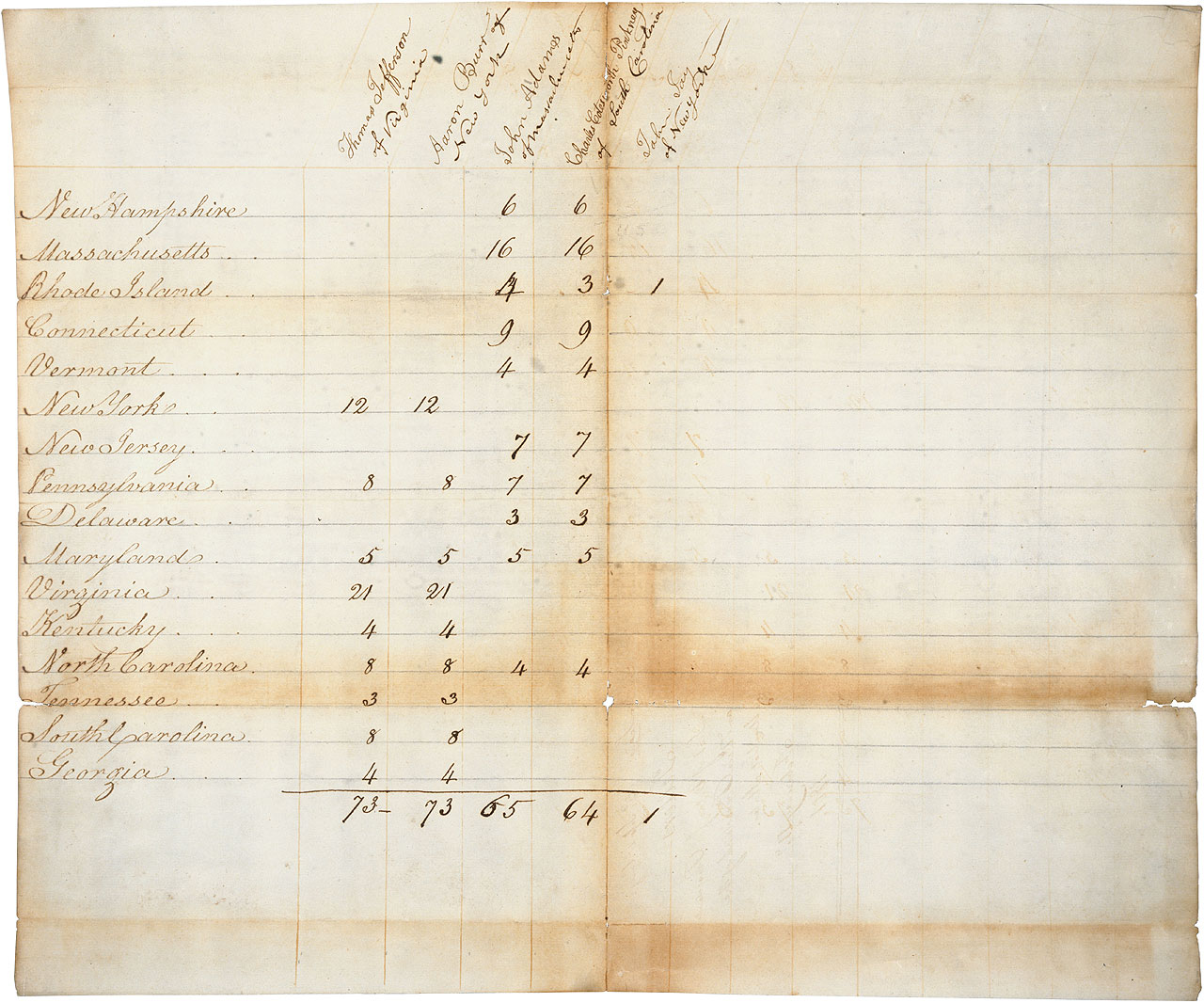

The Votes are in...

Voting for the state legislatures took place over a period of months and did not end until December. When the final votes were in, Jefferson and Burr tied with 73 votes each. As is the case now if there is a tie, the Constitution required the election be determined by the House of Representatives. Then, as today, the vote in the House of Representatives was by state rather than by representative. In other words – each state delegation received only one vote, determined by whoever could command a majority of that state’s representatives. In 1800 the lame-duck Federalists controlled a majority of the states and would determine who won, either Jefferson or Burr. If the deadlock was not broken, the Federalists would potentially continue in power until a new election could be held. Republicans considered action if the Federalists "pervert the election" and refused to give up power. There was talk of calling out the militia in Pennsylvania and Virginia and of a march on Washington. Burr declared queries "unnecessary, unreasonable and impertinent" as to whether if elected he would resign in favor of Jefferson; however, in the moment he declined to step aside.

Feuding Founders

A selection of public and private unflattering quotes the Founders made about each other.

Horrified when he learned some Federalists were pro-Burr, Hamilton fired off numerous letters seeking to dissuade them, writing "for heaven’s sake let not the Federalist party be responsible for the election of this man." In his efforts against Burr, his many letters contained charges of immoral character and anti-democratic intent. In an oft-quoted letter to Henry Gray Otis, Hamilton wrote, "Mr. Jefferson, though too revolutionary in his notions, is yet a lover of liberty and will be desirous of something like orderly Government" (whereas) Burr loves nothing but his own aggrandizement and will be content with nothing short of permanent power in his hands." His virulent attacks on Burr counted for less with the Federalists than the rationale Jefferson would create a more "orderly Government" in a transfer of power that would preserve the essential framework of the government.

Thirty-five ballots were cast from February 11 until on the 17th, Federalist James Bayard of Delaware broke the tie on the 36th ballot. Fearful for the future of the Union, he determined to end the stalemate. He was confident after sounding Jefferson out through a third party that as President he would not weaken the nation’s Navy and retain the banking system. (Standing on principle Jefferson publicly stated he would make no promises for votes to become President; however, over ‘dinner table conversation’ may have indicated responses to issues that addressed Federalist concerns). Bayard made known beforehand his intent to withhold his vote, and Maryland, Vermont and South Carolina followed suit. Jefferson was elected President, and there was a peaceful transition of power.

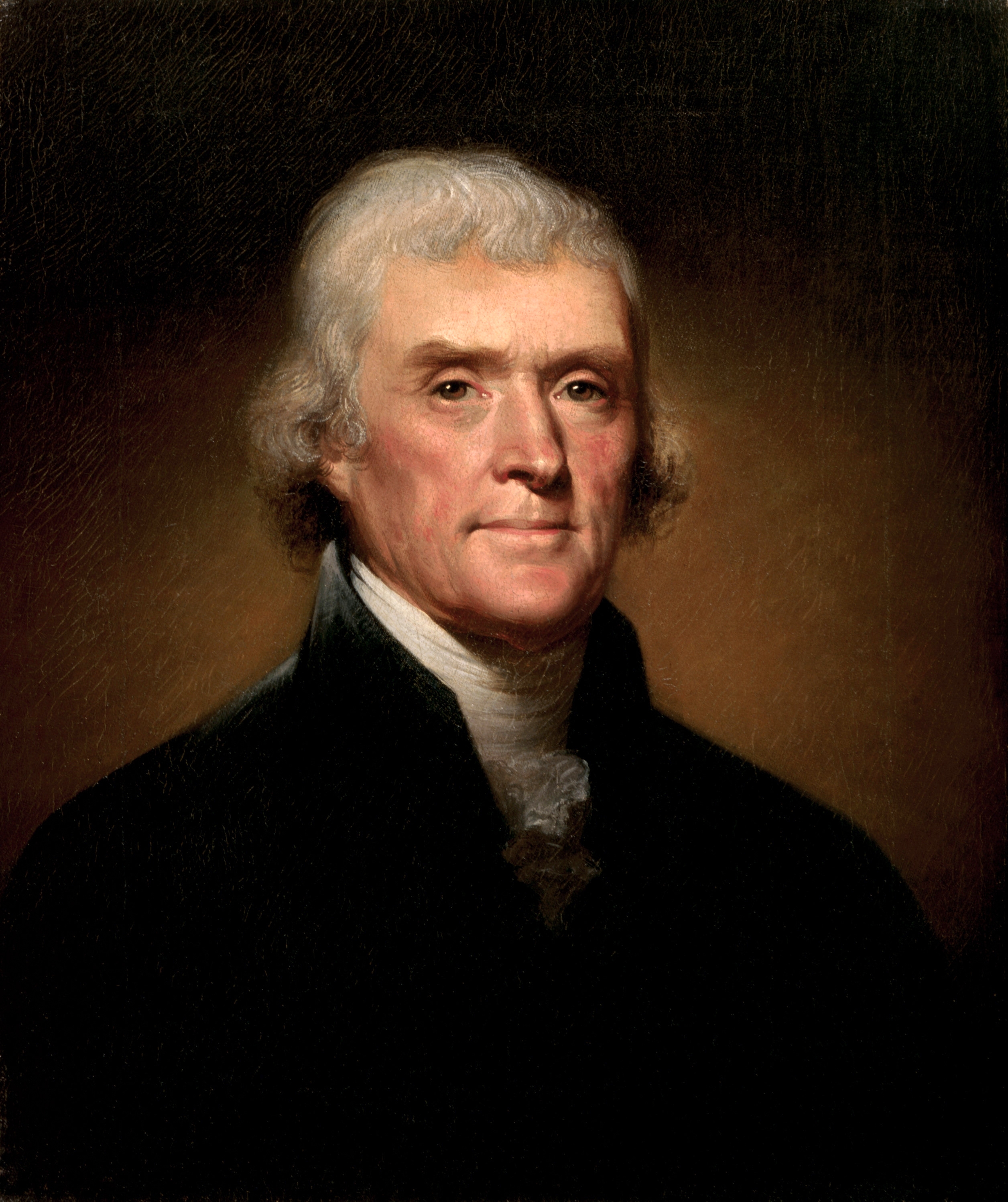

In the aftermath of the election, Jefferson did much to instill harmony among his fellow citizens. In his first Inaugural Address he signaled his intent, "...every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle.... We are all Republicans, We are all Federalists." He retained Federalists in government appointee positions – some 300 were his to apportion – unless individuals were corrupt or using their office for political purchase. And he included both Republicans and Federalists in his Cabinet. Jefferson gradually removed support for Burr in favor of other Republican factions in New York whose votes were critical to his political base, and George Clinton became Vice President in his second term. Upon his return to New York, Burr unsuccessfully ran for Governor in 1804. The election was characterized as a "nasty battle" in which Hamilton once again attacked his personal character, calling him "despicable" (a term meaning socially degraded and considered slander). Burr then challenged Hamilton to their fateful duel. Their personal animosity ended with Hamilton’s death and Burr’s ruin, but during the election of 1800 their differences influenced Jefferson’s election as President!

This blog post was made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this program do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

This blog post was made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this program do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Jefferson's bust of Alexander Hamilton

Livestream: Hamilton and Jefferson