Hiding in the Archives - Identifying a Priceless Jefferson Manuscript of 1776

“Rebellion to tyrants is Obedience to God” – We have come to think of this impassioned phrase as distinctly Jefferson, but there’s more to this story.

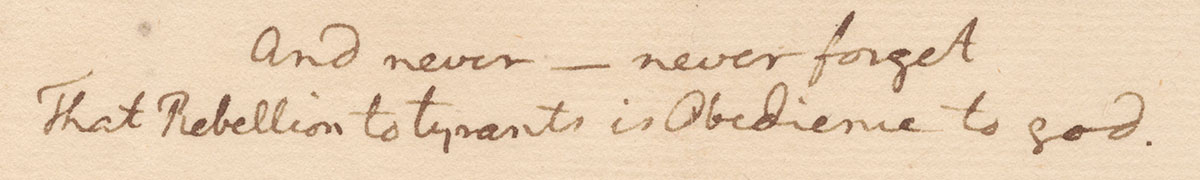

“Rebellion to tyrants is Obedience to God” – We have come to think of this impassioned phrase as distinctly Jefferson, but there’s more to this story.

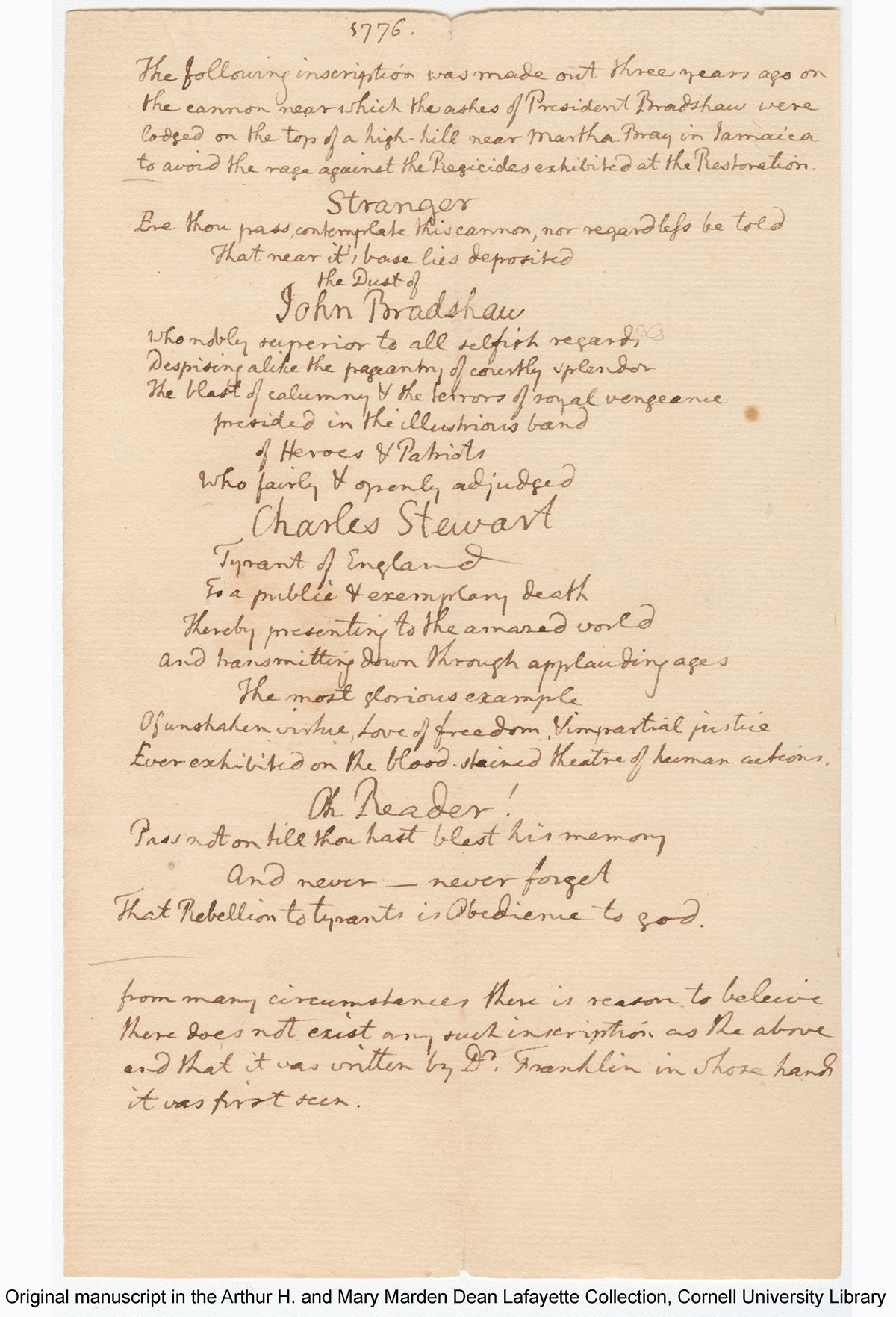

In December 1775 the Pennsylvania Evening Post included a brief transcription of what was said to be the epitaph of the famed regicide John Bradshaw.

As was common at the time, other newspapers around the colonies picked up and published the “epitaph” over the next several months. Even though some believed it was a hoax, and quite possibly the work of Benjamin Franklin, it nevertheless struck the young revolutionary Thomas Jefferson when he first saw it in 1776.

On July 4th of that year, the same day they voted to adopt the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Congress selected Jefferson, Franklin, and John Adams for another task, this time to design “a device for a seal for the United States of America.” It was while they worked together that Jefferson copied out the “epitaph” shown him by Franklin.

On July 4th of that year, the same day they voted to adopt the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Congress selected Jefferson, Franklin, and John Adams for another task, this time to design “a device for a seal for the United States of America.” It was while they worked together that Jefferson copied out the “epitaph” shown him by Franklin.

The design submitted for consideration included the last phrase, as Jefferson wrote it, “Rebellion to tyrants is Obedience to god.” When the final design was chosen several years and two more committees later, it did not include these words. But Jefferson did not forget them and chose the phrase to surround his initials on his personal seal.

The design submitted for consideration included the last phrase, as Jefferson wrote it, “Rebellion to tyrants is Obedience to god.” When the final design was chosen several years and two more committees later, it did not include these words. But Jefferson did not forget them and chose the phrase to surround his initials on his personal seal.

After Jefferson’s death fifty years later, his grandson-in-law Nicholas Trist came across Jefferson’s transcript of “the epitaph on Bradshaw, written on a narrow slip of thin paper” in a dust-covered trunk at Monticello. Jefferson’s family was preparing to leave Monticello in 1828 and Trist was making a sweep of the property looking for anything Jefferson had written. Even the scraps consigned for use in the privies had been gathered up.

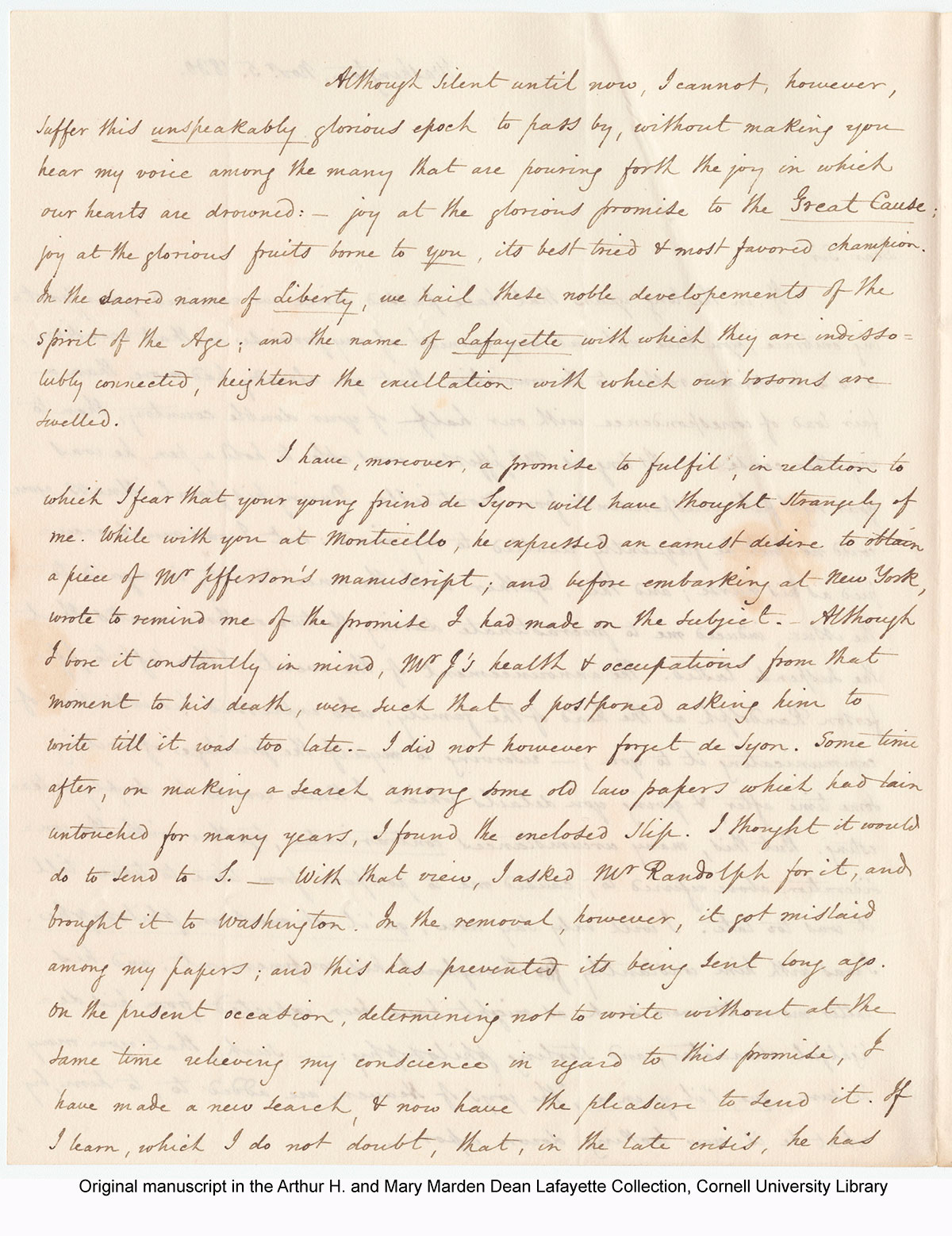

Trist found the “epitaph” while making this hunt, but later misplaced it when he and his family moved to Washington, D.C. Finding it again in November 1830, he thought it was just the thing to send to Lafayette’s friend, Francisque Alphonse de Syon, who had visited Jefferson with Lafayette in August 1825. Just as the young Frenchman was about to leave, he had asked Trist for “a piece of Mr Jefferson’s manuscript,” but Trist had forgotten about the request until events in France reminded him. Now he thought that this particular document, with its call for “Rebellion to tyrants,” might resonate with a young man whom Trist felt sure had “borne himself in a manner worthy of the spirit of the inscription” during the “Three Glorious Days” of the French revolution of July 1830. He enclosed this unsigned Jefferson manuscript in a letter to Lafayette, hoping that that man could forward it on to de Syon.

When the first volume of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson was published in 1950, founding editor Julian Boyd was able to include a transcript made from Jefferson’s original, then still in private hands in Paris, but he never saw the manuscript. Over time its ownership transferred to various collectors around Europe, and gradually its location became unknown. The manuscript was seemingly lost.

As managing editor of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series, one of my duties is to acquire letters written by Jefferson’s family and friends for inclusion in another of our publications, the Jefferson Quotes & Family Letters website. One such request for a family document unexpectedly returned an image of this original Jefferson manuscript, still enclosed in the letter Trist sent to Lafayette in November 1830. Cornell University acquired the Trist letter, along with hundreds of other Lafayette manuscripts, in the 1960s, but neither the enclosure nor Jefferson’s authorship of it were mentioned in the collection’s finding aid. Jefferson’s missing “epitaph” had been hiding in the middle of this letter for more than fifty years. Unsurprisingly, the archivists at Cornell were pleased to learn of its presence in their archive! The collection's finding aid has since been updated.

This hoax, this bit of “Dr. Franklin’s spirit-stirring inspiration,” as Trist called the “epitaph,” meant a great deal to Jefferson in 1776, and its sentiments echoed in his own writings throughout the course of his life. Now, it reminds us of all that was at stake when Jefferson copied it out, when he and his fellow members of the Continental Congress voted in favor of independence and risked everything in their own “Rebellion.”

Related