Five Fascinating Religious Texts from Jefferson's Library

Thomas Jefferson’s relationship with religion was...complicated, to say the least. People still argue over what he may or may not have truly believed, but one thing is clear: Jefferson gave religion a lot of thought. In the British Empire, the king served as both head of state and head of the Church of England, but Jefferson wanted something different for the United States. He wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the first law anywhere in the country to establish a separation of church and state. When designing the University of Virginia, he made it a secular university with a library instead of a chapel at the center. And when it came to his own religious beliefs, he once wrote that "it is known to my god and myself alone.” While we may never truly know what Thomas Jefferson personally believed, the books he left behind give insight into his extensive study of religion. His library (at one point over 6,000 books!) included a large collection of texts about religion, from all different points of view. Here are five of the most fascinating:

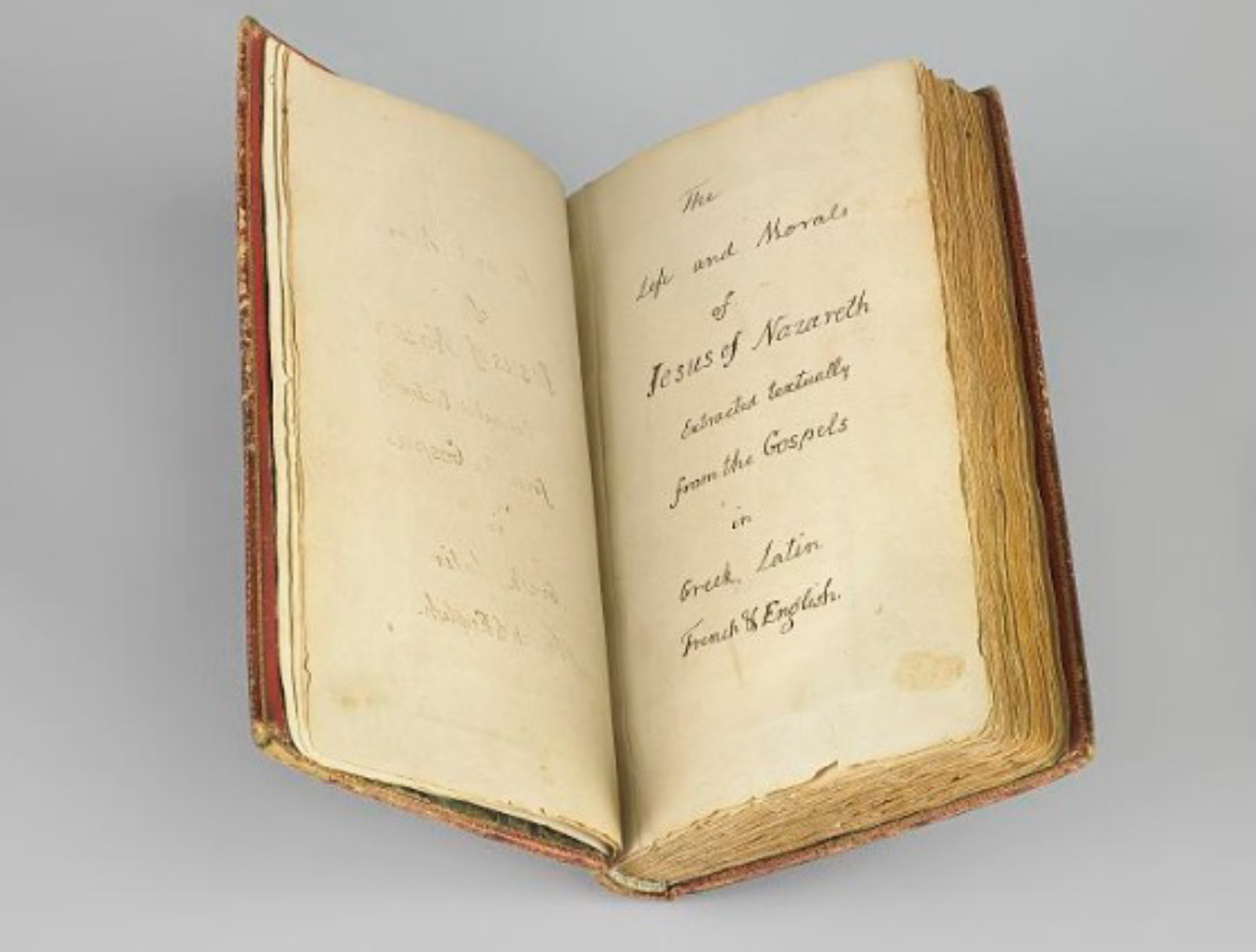

The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, aka “The Jefferson Bible” (1820)

Jefferson put together this book himself, using not only an English copy of the Bible, but also French, Latin, and Greek copies. He literally took a razor to these biblical texts in order to cut out the passages about Jesus’ life that he thought were the most founded in reason and science and paste them together to form an edited biblical text. In other words, he left out anything having to do with miracles, including the resurrection. He never intended “The Jefferson Bible” to be published and only used it for his own reference. You can see how such a book may not have gone over well with his Christian friends and neighbors – not to mention what an absolute gift it would have been to his political enemies. Imagine all the scandalous pamphlets that could have been published – the nineteenth century version of hot Twitter takes!

A New Pantheon: or, Fabulous History of the Heathen Gods, Heroes, Goddesses, etc (1753)

Just as I had to read The Odyssey in high school, students in Jefferson’s time would have been expected to study ancient history, philosophy, and religion. Only they had to do it in the original Greek and Latin. While Jefferson would have viewed the ancient Greek and Roman stories of riding around on winged horses and heroes slicing and dicing their way through snake-haired women who were just trying to mind their own business with his usual skepticism of the supernatural, there’s no doubt that these classical influences colored every part of his life. You can see it in his architectural designs, his musings on human nature, and the artwork he collected.

Pensees Morales de Confucius (French Translation, 1782)

I love getting to surprise visitors with this book - a French translation of the sayings of Confucius. He was a philosopher who lived in China about a hundred years before the Greek philosopher Socrates. Depending on who you ask, Confucianism is a philosophy or a religion or... both. Either way, some Confucian ideas would have had definite appeal to Jefferson: the importance of education, the emphasis on agriculture over commerce, or perhaps most of all, the ideal of the “true gentleman,” someone who was noble because of their moral integrity, not because they happened to be born into the right family. All of these were ideas Jefferson supported in his vision for the new nation.

Qur’an (English Translation, 1764)

Jefferson purchased a copy of the Qur’an during his college years at William & Mary. He would have had little personal experience with Muslims (not that there weren’t any in early America – it’s estimated that about 10-15% of enslaved Africans brought to the Americas were Muslims). However, Islam was clearly a topic of interest for Jefferson throughout his life. In defending the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, he said the law was meant to cover “the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan, the Hindoo and infidel of every denomination.” In Jefferson’s mind, religious freedom had to apply to everyone or it wasn’t true freedom.

The Shortest Way to End Disputes About Religion (1716)

It’s over 300 pages long. So much for “short.” However, we ought to cut the author some slack. He was an English Roman Catholic priest writing during a time of political and religious turmoil in the British Isles as Protestants and Catholics wrestled over the throne. There wasn’t going to be a short and simple solution to the problems facing them. These religious disputes would bleed over into the colonies as well, shaping the world that Thomas Jefferson grew up in. He knew humans had been arguing about religion for a long time and probably would continue to do so. The important thing, though, is that through his ongoing advocacy of religious liberty, Jefferson provided Americans from all different backgrounds and belief systems with the right to have these arguments and discussions openly well into the present era.