That Time When Thomas Jefferson Bought "Ready-Made" Shoes...

In mid-September 1817, Thomas Jefferson was preparing to leave Poplar Forest and return home to Monticello, but he had a few errands to run first. He set off for Lynchburg, roughly a dozen miles to the northeast, where he visited the shop of James Newhall.

The thirty-five-year-old Newhall was a shoemaker who had moved to Lynchburg from Lynn, Massachusetts, after the 1812 death of his wife Rebecca. Jefferson purchased from Newhall what was perhaps his first and only pair of “ready-made” shoes. Unfortunately, they didn’t fit, being too short and narrow, and Jefferson returned them the next day, with a somewhat exasperated note that got me to wondering: where did most people get their shoes, what did those shoes look like, and who made them?

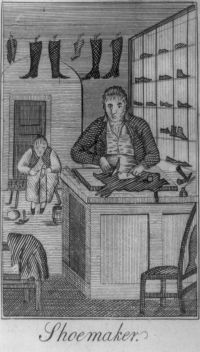

The first shoemakers, or cordwainers, came to Virginia early in the seventeenth century, and they appeared at roughly the same time in the northern colonies as well. The set-up was similar to other trades, with the master, journeymen, and apprentices working together in the master’s home or adjoining shop.

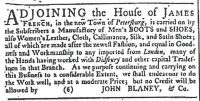

Eighteenth-century newspapers show that the business was booming and highly competitive. Early on, connection to a renowned London shoemaker could guarantee the success of a shoemaker’s business in the colonies, as John Blaney hoped when he advertised in the Virginia Gazette in December 1775 that he’d “worked with [John] Didsbury and other capital Tradesmen” before emigrating to Williamsburg.

Ads placed in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Virginia newspapers reveal that the demand for shoes kept master shoemakers always on the lookout for additional experienced journeymen and willing apprentices.

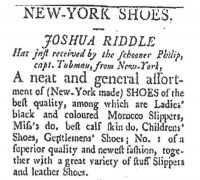

Blaney and some of his colonial competition made and sold “fine” shoes and boots for gentlemen, and ladies’ shoes “made after the latest fashion.” Merchants, on the other hand, sold a variety of goods, typically advertising “a general assortment of SHOES,” both “coarse and fine,” ready-made and recently imported from Europe, and later, made in the United States, packed into barrels and sent down from northern ports like New York and Boston.

These shoes were commonly produced through a system of piecework that existed in the North before larger factories emerged later in the nineteenth century. This cottage industry relied on male and sometimes female workers in different small shops, or sitting by their own firesides, to produce the soles and the uppers separately, after which the pieces were shipped by the “boss” and later assembled into finished shoes by someone like James Newhall.

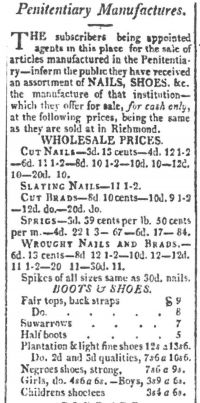

By 1808, a man looking for “coarse” or working shoes in Virginia, had still another option. He could purchase them from the “Penitentiary Store” in Richmond, where he could buy individual pairs or purchase in bulk for his enslaved workforce.

The research of Lucia Stanton, former Shannon Senior Historian at Monticello, has concluded that “there were probably always enslaved shoemakers at Monticello,” and these included Shoemaker Phill (d. 1809), his grandson Barnaby Gillette (1783–after 1827), and Shepherd (1782–after 1827). It is unclear whether Jefferson furnished his slaves only with shoes made at Monticello. He stopped recording the dispersal of shoes on his annual clothing rations lists after 1799.

Often when we think of men’s eighteenth-century shoes, we envision black leather with buckles. Jefferson certainly wore those. Over the course of his lifetime, he recorded in his memorandum books numerous purchases of different types of footwear, such as “Didsbury shoes,” “Morocco slippers,” “pumps,” “mockessens,” “galoches,” “slippers of waxed leather…for walking in the garden,” and of course boots for riding.

After Jefferson retired to Monticello for the last time in 1809, his tastes and needs simplified. While out surveying the work on his farms, he still wore tall, low-heeled leather riding boots. Otherwise, he favored “Morocco slippers” or thin-sol

ed, soft leather shoes that tied at the ankles with “shoe strings,” like those seen in this 1801 engraving after a portrait by Rembrandt Peale.

In fact, Jefferson had been particularly known for wearing the latter during his presidency, and some newspapers of the time remarked on this unadorned shoe as evidence of his republicanism.

Although “ready-made” shoes had been available for many years, Jefferson generally preferred to have his shoes made for him. Up through the early 1800s, shoes were made upon “straight” lasts (wood, and later, cast-iron molds with no distinction made for left or right). Jefferson’s “custom made” shoes were probably also made on straight lasts, matching his feet in length and width, and perhaps even marked with his name and set up on a shelf in, for example, the shop of John Minchin–the Washington, D.C., shoemaker Jefferson favored while he was president. Jefferson would have preferred soft, thin leather shoes not only for comfort but because such shoes would have conformed more quickly to the shape of his feet than those of thicker leather. This also meant that they would not wear as well and would need to be replaced more frequently.

In his retirement, Jefferson generally bought his shoes and boots from the same merchants and shoemakers in Charlottesville. So what prompted him to take a chance with James Newhall’s “ready-made” shoes while he was away at Poplar Forest, rather than waiting a few days until he was back at Monticello? Newhall’s shoes cost Jefferson $2.75, but his memorandum books reveal that he generally paid between $2.50 and $3 per pair in Charlottesville, so cost was probably not a factor. Perhaps he was curious about the innovation of “ready-made” shoes? Despite the fact that Newhall’s shoes were so small that Jefferson could “barely” get them on, he was willing to try another pair, “a good size larger and longer.”

Or maybe the shoes he’d brought with him were suddenly and unexpectedly unwearable.

There’s no way to know for certain, although I wonder if it may have had to do with the very eventful trip Jefferson made to Natural Bridge with his granddaughters Cornelia and Ellen the month before. Maybe he was wearing his riding boots through this series of “disasters & accidents,” as Cornelia described that journey, but what if he had been wearing his laced shoes instead? During that trip, he had had to walk a great deal more than he’d probably anticipated, through mud, over rocky terrain, and across make-shift bridges. Perhaps Jefferson wore out his thin, soft leather shoes on that rather adventurous trip?

Selected Resources

- Thomas Jefferson’s letters and memorandum books, available at Founders Online

- Linda Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America (2002)

- Carl Bridenbaugh, The Colonial Craftsman (1950; reprint 1990)

- Anne Buermann Wass and Michell Webb Fandrich, Clothing through American History: The Federal Era through Antebellum, 1786–1860 (2010)

- Margaret Anthony Cabell, Sketches and Recollections of Lynchburg by the Oldest Inhabitant (1858)

- David N. Johnson, Sketches of Lynn: or, The Changes of Fifty Years (1880)

- Ann Smart Martin, Buying into the World of Goods: Early Consumers in Backcountry Virginia (2008)

- W. C. Morgan, Shoes and Shoemaking Illustrated: A Brief Sketch of the History and Manufacture of Shoes from the Earliest Times (1897)

- Lucia Stanton, Free Some Day: The African-American Families of Monticello (2000)

- Lucia Stanton, 'Those Who Labor for My Happiness': Slavery at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello (2012)